The Soviet weightlifting systems from the 1960s up to 1990 were known for breaking many world records, as well as for creating athletes with longevity. Pavel Tsatsouline translated the Soviet literature and training methods, and in doing so, found that wavy patterns of volume and intensity were some of the keys to the Soviets’ dominance and durability.

I was fortunate to learn straight from Pavel himself about the Soviet secrets of dominance and longevity during this time period.

RELATED: The Barbell War: How the Soviets Ousted American Weightlifting

Soviet Weightlifting Longevity

Leonid Taranenko won his first Olympic medal in 1980 and his last in 1992 at the age of 36. (He is not the only older Soviet lifter, either. Vasily Alexeev also set his last world record at age 36.) Taranenko’s combined total in 1988 for the snatch and clean and jerk was 475kg (1047 lbs.). This is the heaviest ever lifted in a competition.

Leonid Taranenko

Taranenko’s record is no longer in the record book, though, because the International Weightlifting Federation restructured the weight classes (the 90kg class was changed to 91kg and then to 95kg).

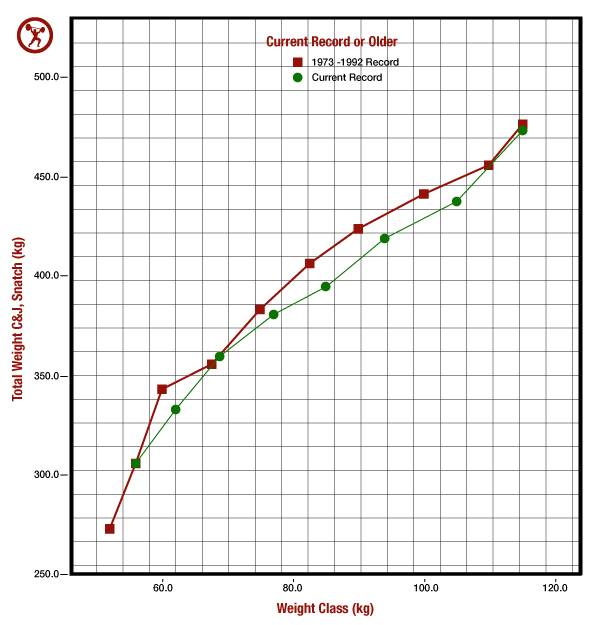

In the figure below, I charted current records against records from 1972 to 1984. The older records are equal to or above the current records, especially for the heavier weight classes. The heaviest lifts (above current records) are all from Soviet athletes.

Empiricism

How did the Soviet system evolve to create such great athletes? They measured everything. Pavel quoted a Soviet scientist who said that physiological data of what works can be found in world records and not in textbooks.

The Soviets also had a ranking system of their athletes. This allowed them to see what programs worked for what level of athlete. There was a great deal of data to analyze and Soviet scientists were put to work doing exactly that.

“How did the Soviet system evolve to create such great athletes? They measured everything.”

Periodization

I recommend you read my colleagues’ excellent synopsis of Western-style periodization programs that came out this week. Most Western systems adjust intensity (defined by percentage of a one-rep max) across the cycle in a linear pattern.

For example, if our lifter had a 1RM clean of 200 pounds, he would start with a lower weight in the first week of training and then build up to higher weights. As intensity increased, the number of lifts or volume would go down. A simple example is Wendler’s 5-3-1 program. In the first week, the person is lifting 5 reps at around 75% of his or her 1RM. By the third week, the person is lifting one rep at 85-90% of his or her 1RM.

RELATED: 7 Markers of a Solid Strength Program

Soviet Programs

Pavel pulled together and analyzed some of the Soviet research literature on how athletes trained in Olympic movements from the 1960s to the 1990s. Some of this work is available as translated versions (e.g., Verkohoshansky’s work). However, a good deal is not available or is poorly translated.

Many of you who know Pavel’s work, know he has a great ability to take the complex and break it down into something simpler.

Here are the basic rules that he found common to the Soviet lifters:

The First Rule: Most Lifts Should Be in the 70-85% Range

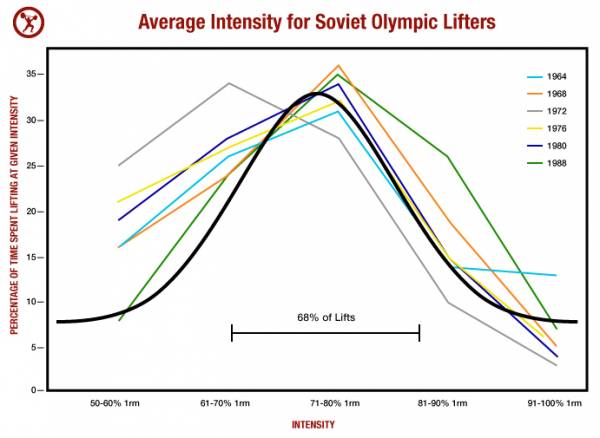

Alexsei Medvedyev, a Soviet scientist of strength, found the intensity of the lifts of Soviet athletes had a repeatable normal curve in the intensity pattern in the data. Around 68% of the lifts came in at around 70-85% of 1RM. Only 5% of the lifts were above 90%.

This range in the moderately heavy range builds strength, and at the same time not going too heavy too often might have been one of the reasons for the Soviets’ longevity. Bulgarian systems tend to have skewed distributions with most of the reps in the 90-100% range. Reps in this higher range are taxing physically and neurologically, and it likely takes more time to recover.

RELATED: Where CrossFit Fails: Training vs. Testing

This rule is probably difficult to follow for many people, as it is tempting to see how much you can lift. However, a great deal of strength can be (and was) built staying in this sub-maximal range.

The Second Rule: More Variability in Volume

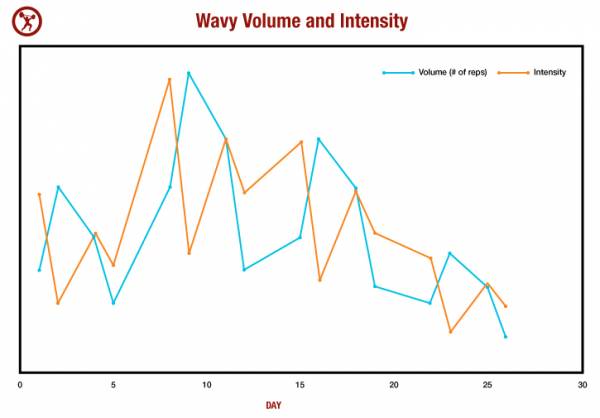

Pavel said, “In the West, the key word in strength planning is progression. In the East, it is variability.” In the Soviet system, the number of reps you lift each day changes weekly and within the week. The idea behind changing volume is that greater variability in how many reps you do is much easier on the body then large jumps in how heavy you lift. This constant up and down of volume can keep an athlete fresh.

Let’s take a look at how to vary volume in practice. If an athlete wanted to do 200 snatches in a month, his or her volume would change each week in a wavy pattern. One week, he or she might do seventy snatches, the next 44, followed by 56, and thirty. Within the week, there are higher and lower volume days, as well.

“The idea behind changing volume is that greater variability in how many reps you do is much easier on the body then large jumps in how heavy you lift.”

The Third Rule: Intensity Varies, but Not in Concert with Volume

Western systems generally have an inverse relationship between intensity and volume. As you lift heavier weights, the number of total repetitions goes down. Within the Soviet systems, these two variables are uncoupled. Thus, you might lift in a heavier range (for low reps), but complete multiple sets.

Some Western systems (e.g., Poliquin and Rhea) have discussed nonlinear systems where intensity changes within much smaller cycles (maybe within a week). However, these systems control for volume to keep it consistent. Thus, the only variable that is non-linear or wavy is intensity (% of 1RM).

The Fourth Rule: Don’t Worry About How You Feel

There are some interesting articles on how CrossFit and other contemporary programs tends to reinforce unhealthy goals, such as getting a certain number of reps in for a time and how this breeds the idea that you need to feel broken at the end of each workout. But these “feelings” don’t bring about long-term strength growth.

“The Soviet training programs doesn’t care about your feelings and neither should you.”

Similarly, in strength programs, people often don’t feel right if they have something left over after a workout. People feel really good if they can do more (weight or reps). The Soviet training programs doesn’t care about your feelings and neither should you.

If you are following a program with volume that changes, you will feel good some days, as if you want to do more. Those days are built into the system so you can continue doing more next week, next year, and ten years from now. The same goes for intensity. It might be tempting to push into the 95% range or go for a new 1RM. But if your programming doesn’t say to do it at that time, then you shouldn’t do it.

Take Home

I left out many of the details on how to create a good Soviet-style program as it can be complicated to calculate the plan of variability for intensity and volume (for a month and for a week). But to be clear: variability does not mean randomness. There is a distinct pattern in the data above.

RELATED: Why the CrossFit Hopper Model Is Broken

An athlete or coach also has to calculate competitions and when to do high-intensity lifts (i.e., 90-100% of 1RM). Pavel is working on a new book and I imagine he will simplify the process greatly for us. Here are the three things that I hope you get from this article:

- Lifting sub maximal weights is the best way to build strength without the eventual recovery that would be needed from attempts at one rep maximums.

- Use variability in intensity, but most importantly in volume.

- In a scientific approach to lifting, don’t rely on how you feel. Stick to the plan.

As someone who has tried a program designed by Pavel in this type of format, I can say there was definitely a great deal of strength gained. I followed it completely and I liked the days when there was limited volume. On days when volume and intensity were both higher, I learned to rest longer between sets and plan for longer workouts. These types of programs also lead to a great deal of variability in time you need to spend at the gym.

RELATED: Rest Between Sets: How Much Do You Need?

References:

1. Medvedyev, AS., 1986. A System of Multi-Year Training in Weightlifting: Sistema Mnogoletnyei Trenirovki V Tyazheloi Atletikye. Sportivny Press.

2. Poliquin, C. 1988. “FOOTBALL: Five Steps to Increasing the Effectiveness of Your Strength Training Program.” Strength & Conditioning Journal 10 (3): 34–39.

3. Rhea, M. R. et al., 2003. “A Comparison of Linear and Daily Undulating Periodized Programs with Equated Volume and Intensity for Local Muscular Endurance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association 17 (1): 82.

Photo 1 by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1986-0706-018 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 2 courtesy of Shutterstock.