Many workouts are described as Tabata-style workouts because they use a :20 on/:10 off protocol. But the original research had other features related to its success. Planks for twenty seconds followed by ten seconds rest might be a good workout, but it is a different workout from the original research.

Furthermore, Tabata workouts were done at maximal effort and should not (and may be physiologically difficult to) continue past eight sets. Thus, an hour-long “Tabata” workout is not a Tabata workout. To get the benefits of high-intensity, short-duration workouts, it is wise to investigate the original research and modern research.

As such, I’ve put together an overview for you, so we can walk through the origins of Tabata workouts, why and how they worked, and how some other intervals may (or may not) work for you, as well.

“Planks for twenty seconds followed by ten seconds rest might be a good workout, but it is a different workout from the original research.”

Dr. Tabata’s Original Research

Izumi Tabata had been publishing research on the aerobic and anaerobic systems prior to his seminal work. He put people through many different sprinting-type protocols to see how and when the different energy systems of the body were used. ATP, the key molecule used for energy production, is synthesized by both aerobic and anaerobic processes (in different ways). Tabata aimed to find a training program that would be the most efficient in improving this synthesis.

RELATED: Go Anaerobic: What It Is and Why to Do It

In the early 1990s, he collaborated with Irisawa Koichi, the Japanese speed skating team coach who had developed a protocol of short maximum bursts of sprints followed by short periods of rest. The program seemed to maintain and improve peak performance in elite speed skating athletes, so Tabata wanted to test the protocol with athletes at different levels.

A 4-Minute Protocol with Maximal Effort

The initial Tabata Workout paper from 1996 examined two groups of amateur athletic males in their mid twenties:

- The first group pedaled on an ergometer for sixty minutes at moderate intensity (70% of VO2 max). Similar to a long jogging session.

- The second group pedaled for 20 seconds, followed by 10 seconds of rest, for 4 minutes (completing 7 to 8 sets total) at maximal effort. The key phrase is maximal effort, as each interval was expected to be a sprint. If athletes could not keep up the speed requirements, they were stopped at 7 sets.

Both groups worked out for 5 days a week for a grand total of 5 hours a week or 20 minutes. The protocol lasted for 6 weeks.

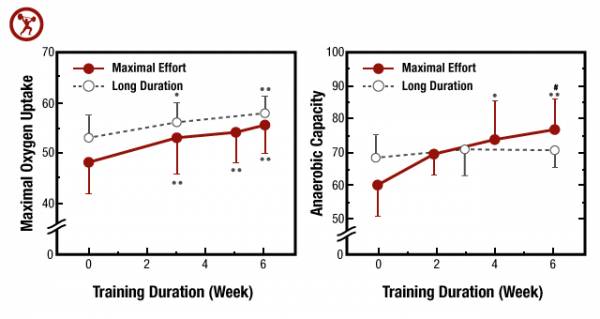

In the above figure, the graph on the right shows a measure of anaerobic process. As expected, the Tabata-style sprinting group improved their performance while the long-duration group did not. It makes sense given that the sprints use a lot more anaerobic processes and you could imagine these becoming more efficient with sprint training.

RELATED: Sprint Intervals Increase Power, Aerobic and Anaerobic Performance

The graph on the left shows the results of oxygen uptake, which is a measure of how efficient people are at aerobic activities (the more oxygen we can take in, the more efficient our aerobic processes will be). Both groups improved on this measure in similar fashions (the red line shows the Tabata-style maximal-effort group). This result was expected for the long-duration group as they were specifically training for this goal. The result for the group doing sprints was surprising in that they improved in a similar fashion.

Thus, it seems that a four-minute maximal intensity Tabata workout had the same aerobic benefits as doing a sixty-minute moderate intensity workout. This news was pretty shocking in that you could get two-in-one benefits from only a four-minute workout.

“Things Are Going So Well, Help Me Screw It Up”

Although the above quotation from Dan John was not aimed at Tabata-style workouts, it does summarize much of what has happened. Since the protocol worked so well, maybe adding different exercises would be a good idea, right? If four minutes was good, maybe twenty minutes would be even better? That is exactly what a “study” sponsored by the American Council on Exercise (ACE) tried to determine.

No research is perfect and there is usually good and bad with every study. However, the web article titled Is Tabata all it’s cracked up to be? is not what I would call research. It’s basically a list of a bunch of exercises that participants completed for twenty minutes in a :20 on/:10 off protocol. The “researchers” found that this increased heart rate and other similar outcomes in the one-session study (we could have probably guessed that people working out for twenty minutes would have increased heart rate).

“Since the protocol worked so well, maybe adding different exercises would be a good idea, right? If four minutes was good, maybe twenty minutes would be even better?”

I would not mention such an article except that I found it cited by many sources as research on how to do a Tabata-style workout. It was “published” on the ACE website and seems to be geared for ACE-certified personal trainers. This workout might be good for people and it might have benefits, but putting the name Tabata on it is a great injustice to the original work.

VO2 Max Testing

Similarly I have seen other articles (even an overall good article written here on Breaking Muscle) that recommend exercises such as calf raises and bicep curls as being suitable for a Tabata workout. A person might feel a great burn and be sore from such a workout, but I wouldn’t imagine he or she would experience the same cardiovascular effects found in the original studies.

RELATED: The Tabata Revolution Explained: What, Why, and How to Tabata

Maximal-effort sprint-like activities are a key component for Tabata workouts. Intensity, not duration, is the key ingredient. A person should not be able to go for more than four minutes doing maximal effort.

From Tabatas to Burgomasters and Gabalas?

Kirsten Burgomaster and Martin Gibala have done research on slightly different maximal effort protocols and have found similar results compared to traditional endurance training work. The big difference in their protocols is that they allow for longer rest (often 30-second maximal effort sprints, followed by 4 minutes of rest, with 4 to 7 sets – and only three sessions per week).

Similar to Tabata’s original research, Burgomaster and Gibala have found benefits to aerobic and anaerobic systems. Others have found benefits in fat loss (see here for a good review article). People might also prefer the additional rest in these types of workouts, as well as the lower frequency of training sessions. Four minutes of rest allows for more time for our ATP-PC system to recover and may provide better performance on the maximal effort attempts.

“Four minutes of rest allows for more time for our ATP-PC system to recover and may provide better performance on the maximal effort attempts.”

Are Tabata-Style Programs for Everyone?

Many training programs are built for specific levels of athletes. However, Tabata-style programs have been tested in all different levels of athletes and have been shown to increase performance outcomes in these different groups.

As mentioned above, the original Tabata protocol was created by the Japanese speed skating coach to improve elite athletes’ performance. Similarly, Matthew Driller and colleagues found the protocol improved 2,000-meter rowing time in elite rowers. Anything that improves elite athlete’s performance is pretty impressive, as it is much more difficult to make gains in these groups.

Conversely, a protocol with less relative intensity and lower volume was created for sedentary individuals. They found improvements in insulin sensitivity in addition to similar outcomes in other studies. Thus, the whole spectrum of athletes seems to benefit from this type of protocol.

Keys to Tabata Success

- Sedentary and beginning athletes might want to take a bit more time to warm up and do the workouts with slightly less intensity as an on-ramp to completing a full Tabata protocol. Furthermore, pick exercises with less risk of injury. For example, an exercise bike is probably safer for a sedentary athlete than sprinting. Many people recommend treadmills, but they are slow to speed up and down and might not be the best suited for this training. A rower or swimming is probably a better alternative.

- Intensity is key. The goal is to practice the exercises with maximal intensity for a short duration of time. Don’t worry about your feelings of guilt for not working out longer. Doing more than the specified four to eight sets will not help you in the long run.

- Volume varies depending on goals. If your goal is maximal strength, then doing a Tabata-style workout one to two times a week might be beneficial. If your goal is to build greater endurance, then following the full Tabata-style workout five days a week will be most beneficial.

- Separate strength from conditioning. Do not think of the Tabata or other maximal effort protocols as a way to build strength. Max effort push ups or pull ups might be fun to try every once in a while, but there are more efficient ways to build strength. Your conditioning will be better off if you stick to exercises where you can perform maximal effort type of sprints.

- Optimal exercises might be: bicycling, rowing, swimming, hill sprints, stair sprints, jumping rope, sled push, and sprinting. It becomes a bit more of a gray area on whether kettlebell swings, box jumps, burpees, and other similar exercises are optimal (Maybe a bit easier to rest between reps of the movement; the key is to be able to throw maximal effort into the movement).

RELATED: Tabata Intervals: An Effective Protocol For Cyclists and Endurance Athletes

Further Reading

- Simon Kidd ’s excellent article on how to do a cycling Tabata program.

- I like Logan Christopher’s article on why you don’t need to do conditioning, even though I think some of his workouts are conditioning-style based on these protocols.

References:

1. Boutcher, S. H. (2010). “High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise and Fat Loss.” Journal of Obesity, 2011, e868305. doi:10.1155/2011/868305

2. Burgomaster, K. A., Heigenhauser, G. J., & Gibala, M. J. (2006). “Effect of short-term sprint interval training on human skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism during exercise and time-trial performance.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 100 (6), 2041–2047.

3. Burgomaster, K. A., Howarth, K. R., Phillips, S. M., Rakobowchuk, M., MacDonald, M. J., McGee, S. L., & Gibala, M. J. (2008). “Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans.” The Journal of Physiology, 586(1), 151–160.

4. Driller, M. W., Fell, J. W., Gregory, J. R., Shing, C. M., & Williams, A. D. (2009). “The effects of high-intensity interval training in well-trained rowers.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 4(1), 110–121.

5. Gibala, M. J., Little, J. P., Van Essen, M., Wilkin, G. P., Burgomaster, K. A., Safdar, A., … Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2006). “Short-term sprint interval versus traditional endurance training: similar initial adaptations in human skeletal muscle and exercise performance.” The Journal of Physiology, 575(3), 901–911.

6. Hood, M. S., Little, J. P., Tarnopolsky, M. A., Myslik, F., & Gibala, M. J. (2011). “Low-Volume Interval Training Improves Muscle Oxidative Capacity in Sedentary Adults.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(10), 1849–1856. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182199834

7. Medbo, J. I., & Tabata, I. (1989). “Relative importance of aerobic and anaerobic energy release during short-lasting exhausting bicycle exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 67(5), 1881–1886.

8. Tabata, I., Irisawa, K., Kouzaki, M., Nishimura, K., Ogita, F., & Miyachi, M. (1997). “Metabolic profile of high intensity intermittent exercises.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 29(3), 390–395.

9. Tabata, I., Nishimura, K., Kouzaki, M., Hirai, Y., Ogita, F., Miyachi, M., & Yamamoto, K. (1996). “Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2max.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28(10), 1327–1330.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 “Striving for the best” by Fort Carson Atribution 2.0 Generic License

Photo 3 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.