Winter is here in the northern hemisphere. As a cyclist I have to adapt my training for the offseason. In this article, I will explain how to apply the FITT principles to your training. It’s all about listening to your body and understanding how it adapts to stress cycles in training.

FITT is an acronym for Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type. These concepts form an effective framework to adopt when planning your training sessions this winter. I apply it to my cycling training but the principles hold for any type activity where you are looking to create or maintain peak performance.

- Frequency is the number of training sessions per span of time. For example, how often you will train per week.

- Intensity is the level of difficulty of the session. This might be an intense interval session in a class, or a less intense endurance ride.

- Time is the duration of the session. Most gym classes or turbo training sets tend to be about an hour long. A weekend morning ride with a club is usually two or more hours.

- Type is the actual training activity. This might include weight training, an interval-based indoor cycling class, a cycling endurance session, or session concentrating upon flexibility or recovery.

Frequency Requires Balance

Perhaps the most key of these concepts is frequency. Frequency is much more than how many times per week you decide to train. Too many training sessions per week will result in over-training and a decline in performance. Too few sessions per week will not provide enough stimulus to adapt and improve performance. The key to getting the best results from your training is to build your sessions around how long it takes to adapt after each one.

I have deliberately used the word ‘adapt’ here, rather than ‘recovery.’ Recovery might be what you do after an illness, or you may feel recovered after a few days’ rest following a training session. That is not adaptation. Adaptation is what happens when you provide a sufficient training stimulus to the body to cause it to get better at a particular activity. In this case, we are looking for an adaptation to improve cycling.

The time it takes your body to adapt can depend upon several factors such as your age, the intensity and duration of a training session, the type of training, your current level of fitness, exercise history, and lifestyle stresses. Everyone is different.

The Effects of Frequency on Adaptation

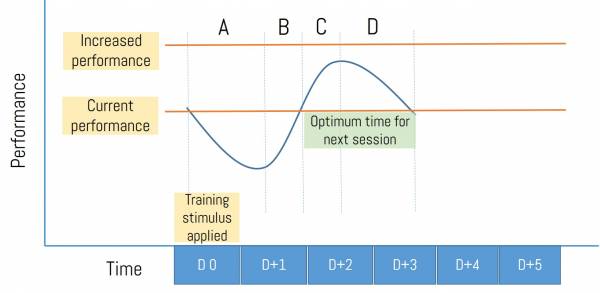

The chart below shows the change in your performance as a training stimulus is applied at A, then the adaptation occurs at B and C. At C, the adaptation (if sufficient stimulus has been applied) will result in an improved performance. At D, if no further training stimulus is applied, your performance will start decline, and if left too long will sink below where you started. A good place to apply the next training session will be at the sections labelled C and D, so that you can continually build upon the previous improvement.

Using this chart as an example, assume that you undertake an intense session on day zero. This might be a long session, or an intense session that requires a longer time for the adaptation to take place. In the chart above, adaptation starts to occur at B, two days later. A good place for further training would be on days three and four. Day five is too late, as some degradation will have occurred, and training at this point is likely to just maintain the status quo.

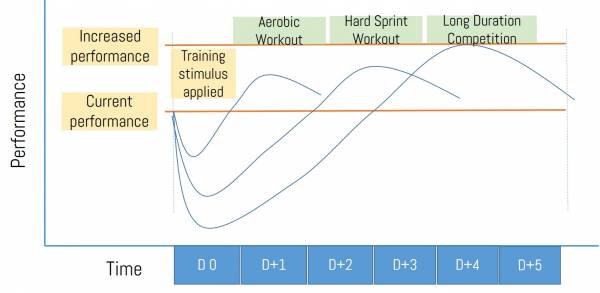

Now let’s say that the training stress is less severe, and adaptation starts to occur on day one. A good place for further similar training would be on days two and three. Day four would be too late to enhance performance.

In practice, this might result in a schedule that comprises an intense session on Sunday, followed by two less intense sessions on Wednesday and Friday, resulting in three sessions per week. Any more sessions than this might mean that adaptation has not occurred to build performance. Any fewer sessions than this might result in no improvement, but maintenance of the current position.

If your schedule only allows two sessions per week, these would need to be a little more intense or longer duration. To take advantage of the adaptation curve, these might be on Sunday and Thursday.

When Should You Go Again?

Your optimum time to re-train will also depends on your previous training. There are a few ways you can find out when your optimum time for adaptation might occur.

One very simple way is to use an existing feature within a sports training watch or app. Some devices have a feature that will calculate or estimate your approximate training load for a session, and your accumulated load for the week, and suggest a time when it would be appropriate to undertake further training. If used consistently for all your training sessions, you will have a systematic way of determining the frequency of your training.

Another way is to use your resting heart rate. This will tend to be higher as your body repairs and re-generates the tissues necessary for adaptation, and will return back to a lower level when adaptation has is complete. You only need a stopwatch and a log book to do this. To obtain best results, you should take your resting heart rate every day at the same time, so that you become familiar with the ranges of heart rate you would expect to find. Your values will be unique to you.

For example, over a period of measuring consistently for two or more months, you may be able to establish a guide that that if your heart rate is in the range 50-55, you can train again. If it is above 55, then only light training or no training should take place, and if below 50 then you may be undertrained.

Another way might be to estimate your training load from some metrics. An intense session of one hour could be given a score of one hundred, two hours a score of two hundred, and so on. A less intense session for an hour might be given a score of fifty. Then for every one hundred points, you allow one day to adapt.

This last strategy will not be as accurate as using your heart rate or a digital algorithm in a training device, but may be a useful place to start. The main thing is to listen to your body. If you are still aching from your previous session, it is unlikely that you will have adapted fully.

Looking to go it alone this winter? Here’s how to get started: