Over the past few years, we’ve seen a ton of new carbohydrate powders hitting the dietary supplement market. There are probably a few reasons for that, but if I were to paint them all with the same brush, the main reason would be economics.

You can find carb powders in the aisle of misfit toys at your local supplement store.

Profit margins on high-quality protein are stagnating (if not shrinking), while profit margins on nearly everything else have increased. There is far more profit to be made in carbohydrates than protein, believe it or not.

Why Use Carbohydrate Powders?

If you’re training more than once per day, you should probably be using a high-quality carbohydrate powder. If that training is more than simply two weight-training sessions (i.e. metcon or endurance work), then I’d say it’s even more important. If you’re training once per day, three to five days per week, you need to fully replenish glycogen by the following session, unless you’re specifically going low-carb or you’re fat-adapted. In either of those last two cases, since you’re limiting your daily intake, it’s even more important that you make the best possible carbohydrate choices, and that probably involves a high-quality carb powder.

The Economics of Protein

A few years ago, Gatorade, one of the largest beverage companies in the world decided to start marketing a protein supplement. Overnight, they were buying up more protein than the rest of the market combined. As demand at the commodity level increased, so did price – and it never stopped.

Totally anabolic celebration bath!

Unlike other ingredients, most of the major protein sources (whey and casein) come from a finite source (cows). Before whey became known as the premier anabolic protein, it was a cheap throwaway with limited value to the dairy industry. The supplement industry changed that, and here we are two decades later. And while protein powder is getting harder to turn a profit off, carbs have made a huge comeback.

Herbs and vitamins can be synthesized (for the most part), but generally that’s not true of protein – and in the cases of animal protein, farmers can’t simply plant more. Protein keeps getting more expensive, while carbs have remained consistently priced for the past few years. There’s a ten cent increase here or there because of a drought or whatever, but nothing approaching what we see with protein.

I’m not saying this is a bad thing, because economics can drive innovation, and supplementing carbohydrates (the right kind, in the right way) can have enormous positive impact on athletic performance. But because concentrated or isolated whey basically doesn’t exist except for powder form, and carbs are readily available (yams, potatoes, etc.), there is a huge gap between the number of different protein powders we can purchase at the local store versus the number of carb powders.

Athletes and Supplementation

But the availability of carbohydrate powders has steadily been rising in brick and mortar stores. And while that’s due in part to economics, it’s also because of an increased demand. Fat-adapted athletes are starting to figure out how to incorporate specific carbs into their diet. It’s also because we’ve seen functional fitness competitions becoming more common, and these often require two or three workouts per competition, sometimes on multiple consecutive days or even back to back. Therefore, athletes are doing more daily training sessions and finding carbohydrates necessary in between those sessions, especially throughout a weekend of competing.

“[A]thletes training for a fitness competition, training more than once per day, competing in multiple events throughout a day or weekend … all need carb powders to optimize their performance.”

Still, the athletes moving into these types of competition aren’t doing so in numbers that overwhelm the market, so another factor in the relative paucity of carbohydrate supplements on the general market, is that the average consumer is a bodybuilder – or what I call a misguided bodybuilder (people who play a real sport, but follow the routines and advice found in bodybuilding magazines). Because low- and no-carb diets quickly became the standard for bodybuilding contest preparation, carbohydrate powders were relegated to the endurance camp, occupying a Lesotho-style territory at the local supplement store, surrounded by huge jugs of protein powders and smaller tubs of pre-workout stimulants.

Carbohydrate drinks have traditionally been the domain of athletes and this is mostly still the case. Watch any marathon and you’ll see people handing out cup after cup of fluorescent-yellow carb drinks. Far more of that stuff is sold each year than anything you’re going to find in the local supplement store, and until they start dumping whey protein on the winning Superbowl coach, that’s unlikely to change.

Bodybuilders Begin to Catch On

But when the days of mega weight-gain powders were gasping their last breaths, bodybuilders started looking for clean carbs to mix with their whey protein, and those powders made inroads. Straight meal replacement powders also took a beating around this time, when it became obvious that a $3/serving pouch of (whatever) could be more economically homebrewed with carb powders and whey proteins.

And while bodybuilders won’t balk at a $100-250 monthly supplement bill, the market we see for endurance athletes is primarily geared towards race-day use. But the preferred supplement customer is the one who buys a product every month, not twice per year. Again, this is economics at play. Nobody is going to compete with the billion-dollar brands that dominate the carb drinks of the endurance (and athletic) world – but they can attempt to make inroads into the far smaller bodybuilding community, where sugary RTD carbs aren’t popular.

Carbs and Performance

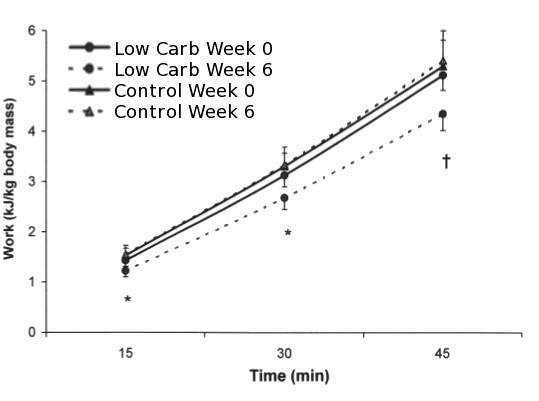

This is also due in part to what bodybuilders discovered early on, but was later confirmed by science: very-low carb diets are great for losing weight, but not for performance. You can retain muscle (or even gain it) while restricting carbohydrates, but performance invariably suffers. A pair of studies funded in part through a grant from The Atkins Foundation confirmed that while subjects could lose a considerable amount of fat, and even gain muscle, the ability to perform high-intensity exercise will suffer (as measured by kilojoules/kilogram of body mass).1,2

Courtesy of “Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab.” 2003 Dec;13(4):466-78. Endurance capacity and high-intensity exercise performance responses to a high fat diet. Fleming J. et al.

High intensity exercise (or HIIT) as a fat-loss modality was first popularized by Shawn Phillips in the ’90s, and within a few years, it was one of the dominant forms of cardio in bodybuilding (not entirely surprising, as it dethroned ass-numbing hours on the stationary bike). As a result, it’s no surprise that researchers investigating low-carbohydrate diets would examine body composition as well as high-intensity performance. These studies were done only a few years after low-carb became de rigueur and Shawn’s HIIT article was published in Muscle Media.

That same magazine also introduced us to the first major carbohydrate evolution: Vitargo. My exposure to Vitargo was a 1997 EAS product called Myoplex Mass. I was a Myoplex user back then and (as you may have guessed) an avid reader of Muscle Media, the EAS-owned bodybuilding magazine where it was advertised. This is how most Americans likely heard of the product, which is patented and owned by a foreign company.

By 1999, there was some interesting data emerging on something called highly branched cyclic dextrin (HBCD), and a study was published where mice were able to swim slightly longer with the consumption of HBCD compared with regular glucose. But this happened not when given prior to exercise, and not when given thirty minutes after starting, only when administered after ten minutes of beginning exercise (basically when it’s useless because nobody bonks after ten minutes).

Exhaustion was deemed when the mouse was unable to surface for a full seven seconds – greater than seven seconds would typically result in death. (Of course, surviving the test also resulted in death, as the mice were decapitated for blood samples and data collection.) Compared to glucose, HBCD produced similar endurance results, despite providing less of a spike in blood sugar and a more stable energy platform.3

“I’m not saying this is a bad thing … supplementing carbohydrates (the right kind, in the right way) can have enormous positive impact on athletic performance.”

After that first study, the research gets, well, weird. Athletes look to supplements to enhance their performance, and the subsequent studies on HBCD drew conclusions based on efficacy related to immunoendocrine responses and perceived exertion, which are great, but are not performance.4,5 These proxy measurements are of little use to athletes when the end result is zero performance increase – but they have served well in producing glossy charts and advertisements that put HBCD into the hands of bodybuilders.

It’s also worth noting that while the authors of the first HBCD paper speculate about the rapid gastric emptying of the carb, subsequent research shows it to hang around in the stomach longer than some other (far cheaper) carbs.6,7 In fact, tested against both maltodextrin and glucose, HBCD doesn’t do anything special for rate of perceived exertion and produces no additional blood glucose.7

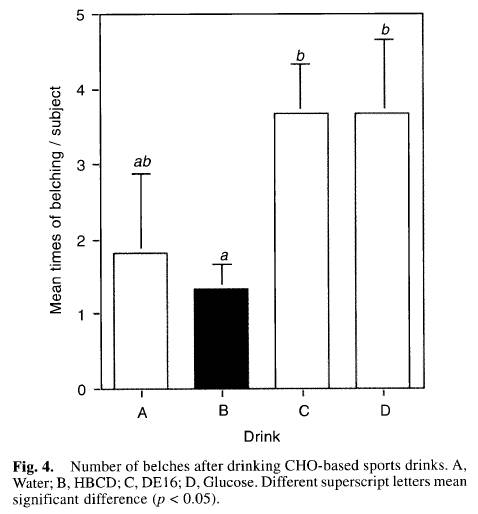

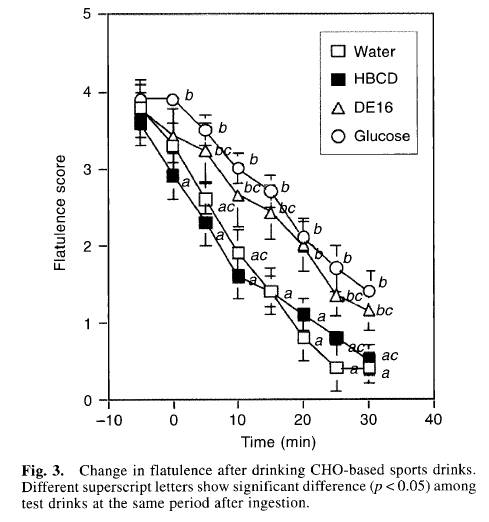

Not a single study on this product gives me any reason to think it’s going to improve performance at all, and certainly nothing makes me believe it’ll do better than stuff that costs far less. The only thing I can say about this product is it’s the first one I’ve seen that includes post-consumption data on how much burping and farting the test subjects owned up to:

Courtesy of H. Takii et al, “A Sports Drink Based on Highly Branched Cyclic Dextrin Generates Few Gastrointestinal Disorders in Untrained Men During Bicycle Exercise.” Food Sci. Technol. Res., 10 (4), 428-431, 2004.

Highly Branched Cyclic Dextrin:

- Has not been shown to increase performance in humans when tested against other carbohydrates

- Does not increase blood glucose better than any of the sports drinks it was tested against

- Empties from the stomach slower than maltodextrin, but faster than glucose

- Shows no benefit to performance above other carbohydrates drinks during exercise in humans

- Shows no benefit to rate of perceived exertion during exercise, when tested against other sports drinks in humans

- A one specific time point (of multiple that were tested), in one study, in rodents, showed a performance increase

Waxy Maize Hits the Market

A few years after the initial data on HBCD was published, we saw waxy maize make it’s first appearance on the market. Here’s how that happened in one representative instance that could serve as a placeholder for how it occurred across half a dozen companies at roughly the same time, with perhaps slightly different wrinkles:

Just as Vitargo was a major evolution in carbohydrates, the first major carb devolution was an attempt to copy it. One of EAS’ sales reps who became familiar with Vitargo during his time at the company (when it was extracted through a patented process from potato starch) went on to found his own company and license Vitargo for use with creatine – but this version happened to be produced using waxy maize as the source material. Waxy maize is a form of corn, but it’s different than the kind you’d see at the local farmer’s market, or being eaten by Michael Jackson as he reads Facebook comments.

“The key is to supply adequate energy for the task at hand … You don’t get extra credit for finishing a race with really high glycogen levels.”

In December 2006, the company in question lost the rights to the product, and launched a competing one, which was simply waxy maize without having undergone the chemical alterations that made it into Vitargo. This fact inspired other companies to market regular waxy maize and make identical claims to Vitargo (which has also been made with barley and various other starches). This is emblematic of how waxy maize got its start on the market and was a form of logic followed by several companies both before and after.

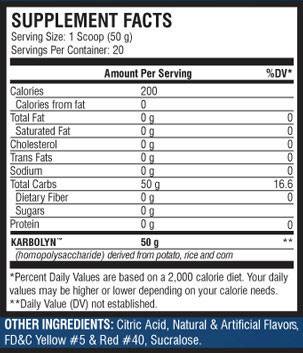

That same year, another company, All American EFX, claims to have released a waxy maize product called Karbo-Lyn, stating on their website, “In 2006, All American Pharmaceutical released Karbo-Lyn, the new patent pending waxy maize type product that is revolutionizing the athletic world.” That write-up gifts us with a mind-boggling 78 references. Out of those 78 references, 55 of them are never actually cited in the text of the article, and almost none are relevant to the shaggy dog they’ve got posing as a scientific article.

Oddly, when I last checked the Karbo-Lyn label (which for some reason, lacks the hyphen in the name found on the website), it didn’t contain any waxy maize at all, unless they’re simply calling it corn, but has added potato and rice, which would make it rather light of the ingredient they claim is revolutionizing the athletic world. Still, I’m pretty sure this stuff is (or contains some) waxy maize.

Breaking down 200 calories of mystery carb.

Data on this particular brand of waxy maize is a bit sketchy because in 2007 and again in 2009, the highly prestigious Bioceutical Research and Development Laboratory (which is owned by the same company as Karbo-Lyn) made public their studies on the product. Both studies failed to be published in any journal and neither was peer-reviewed nor double-blind. There was no recorded performance data in either study, no objective measure of any relevant parameters, and the number of test subjects was far below statistical significance.

Also, both studies were written on a cocktail napkin.

In crayon.

Alright, those last two lines were possibly not true, but the ones before were (except in some meta way where the whole study is a joke). Whether or not there’s any waxy maize in Karbo-Lyn (with or without the hyphen), it’s in a lot of other products and for a variety of reasons. It has been used as a starting material for various engineered carbs like Vitargo, Superstarch, and HBCD, which all have vastly different properties due to the chemical alterations they’ve undergone.

Confusing waxy maize for something that has been made with it, or thinking everything made with waxy maize is similar, is like confusing a bagel with a doughnut because they’re both made with flour. Also, with carbohydrates, even if you’re eating them au natural, like with rice, the way you prepare it can not only change the flavor and texture, but can reduce the calories and change the regular starch into a resistant starch (which makes it act more like a fiber). So while Product X might be waxy maize and Product Y might be made from waxy maize, this tells us little about Product Y.

Market Stagnation and a New Study

Very little of note happened in the carbohydrate market for the years after waxy maize dropped. It remained and remains a popular carbohydrate in the bodybuilding world. Maltodextrin remained dirt-cheap and the go-to carb source for half the supplement world. It’s really not very good because it spikes blood sugar badly, followed by a rapid dip, which makes it a relatively horrible choice if you’re going to use a carb powder as it typically results in a crash or fatigue (although because it sucks so badly, it makes a great carb to use in studies when you want).

If only spelling “carb” with a “k” is all it takes to invent an effective supplement.

Then in 2010, a study was published on something called Superstarch (funded by UCAN, the parent company of the product).8 This particular starch has been modified through a heat/moisture treatment, utilized to modify carbohydrates to more readily be stored as glycogen in children with glycogen storage disease (inability to convert glycogen to glucose in the liver).9,10

Nobody cared about the study. I mean literally nobody. Then we found out, prior to the 2012 Super Bowl, that the New England Patriots had been using it (and probably deflating balls, video taping their opponents play calls, and a bunch of other stuff). We found this out when low-carb guru Dr. Jeff Volek began touting the likely performance benefits of the stuff in Men’s Health:

This more sustained fuel flow has many advantages such as promoting greater use of fat and potentially sparing muscle glycogen…Most sports like football, basketball, tennis, and hockey, require short bursts of high intensity effort that draw on glycogen…So anything that spares their use could translate into performance gains.

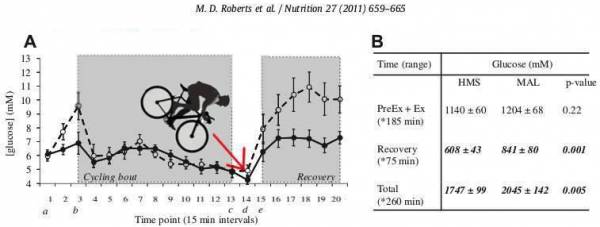

A low-carb guru promoting a carb! It must be pretty awesome, right? Sadly, Dr. Volek himself performed the 2010 study on Superstarch, and there were absolutely no performance gains. Zero. Wait, did you get that last part? Because I’ll say it again for the people in the cheap seats.

Superstarch has been shown in a published, peer-reviewed study not to improve performance by the same person who subsequently opined that its use could translate into performance gains. It also produced one of the most tremendous dips in blood sugar (below baseline) I’ve ever seen.

Here’s how that study went down:

Nine healthy male cyclists participated in a double-blind randomized crossover study – except for the relatively small sample size, this is almost the gold standard of research. Competitive cyclists rode at a predetermined workload amounting to 70% of their VO2 peak. After 150min of steady-state exercise, the workload was increased to require cycling at their individual 100% VO2 peak until they could no longer maintain a minimum pedal cadence of 50 revolutions/min or the subjects’ power output decreased to a point greater than 10% below the prescribed workload.8

So, basically this is like a race situation, where you would be cycling along at a steady pace, and then you make a move for first and have to battle it out. Even though there is some logic behind this product, it didn’t outperform the active control (maltodextrin). But because nobody reads studies, it has been widely promoted as a performance-enhancing carb to athletes. And yes, I’ve heard all of the (implausible) excuses, that it works in this situation or that situation or it works in fat-adapted athletes or this one guy with a podcast (who also happens to sell it). The science is the science, and it works (or doesn’t) the same way whether you believe it or not.

Quoting directly from the study:

- “…tests revealed that there was no difference between the HMS and MAL trials…” (Remember: the HMS was UCAN’s not-so-Superstarch and the MAL is regular old . 40c/lb maltodextrin)

- “There were no differences in serum cortisol AUC values between trials…”

- “There were no significant differences between trials with regard to ratings of perceived exertion at each respective time point…”

- “There were no significant differences between trials with regard to CHO oxidation rates, fat oxidation rates…during the 150-min exercise bout.”

- “…there were no statistical differences in the glucose and/or AUC values during the exercise bout…”

- “Cyclists in the present investigation exhibited similar time-to-exhaustion values during both conditions during the 100% VO2peak sprint that immediately followed the 150-min submaximal bout.”

So what’s going? Maltodextrin sucks and Superstarch seems to have some kind of logic behind it. The problem is that it’s logical but not physiological.*

Carbohydrates and Performance

The key is to supply adequate energy for the task at hand. So let’s say you can run a four-minute mile, with optimal fueling. If you eat a ton of carbs beforehand, you’re not going to run a 3:45 mile because if you’ve got adequate energy stores, adding more fuel doesn’t help. It’s like pouring more gas into an engine that’s already full (car nerds: save me your headshaking and cap-locked comments about turbochargers and superchargers). If you’ve topped yourself off, relative to the task at hand (i.e. enough energy to complete it), adding more carbs past the ideal level won’t help. You don’t get extra credit for finishing a race with really high glycogen levels.

“Because nobody reads studies, [Superstarch] has been widely promoted as a performance-enhancing carb to athletes.”

Whatever the task is, when we’re using carbs as our fuel source, or at least part of our fuel source, we want enough to perform at our maximal level – to take advantage of whatever training adaptations we’ve managed to secure. At that point, extra fuel is no longer a rate-limiting factor. It’s not the thing keeping us from running a faster mile. Extra carbs before your training session aren’t going to help you bench more, either, unless you were already operating at a deficiency.

Where Do We Go From Here?

So we’re back to where we started – athletes training for a fitness competition, athletes training more than once per day, athletes competing in multiple events throughout a day or weekend – they all need carb powders to optimize their performance. Over the past few years, these types of competitions (and athletes) are becoming almost exponentially more commonplace, and they’re realizing they perform better when they’re using a carb supplement. So don’t be surprised if you see a few more rows of carbohydrate powder at the local supplement store, as practicality and economics converge.

*I think I stole that saying from someone, probably Mike Nelson.

Check out these related articles:

- Why It’s Time to Regulate the Supplement Industry

- How Do We Know If Supplements Work?

- 10 Things I Know About Protein That You Don’t

- What’s New On Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. JS Volek, et al. “Body composition and hormonal responses to a carbohydrate-restricted diet.” Metabolism. 2002 Jul;51(7):864-70.

2. J Fleming, et al. “Endurance capacity and high-intensity exercise performance responses to a high fat diet. ” Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003 Dec;13(4):466-78.

3. H Takii, et al. “Enhancement of swimming endurance in mice by highly branched cyclic dextrin.” I. 1999 Dec;63(12):2045-52

4. T. Furuyashiki, et al. “Effects of ingesting highly branched cyclic dextrin during endurance exercise on rating of perceived exertion and blood components associated with energy metabolism.” Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2014;78(12):2117-9. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.943654

5. K. Suzuki, et al. “Effect of a sports drink based on highly-branched cyclic dextrin on cytokine responses to exhaustive endurance exercise.” Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014 Oct;54(5):622-30.

6. H Takii, et al. “Fluids Containing a Highly Branched Cyclic Dextrin Influence the Gastric Emptying Rate,” Int J Sports Med 2005; 26: 314-319.

7. H. Takii et al, “A Sports Drink Based on Highly Branched Cyclic Dextrin Generates Few Gastrointestinal Disorders in Untrained Men During Bicycle Exercise.” Food Sci. Technol. Res., 10 (4), 428-431, 2004

8. Roberts MD, et al. “Ingestion of a high-molecular-weight hydrothermally modified waxy maize starch alters metabolic responses to prolonged exercise in trained cyclists,” Nutrition (2010), doi:10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.008

9. K Bhattacharya, et al. “A novel starch for the treatment of glycogen storage diseases.” J Inherit Metab Dis 2007;30:350–7.

10. CE Correia, et al. “Use of modified cornstarch therapy to extend fasting in glycogen storage disease types Ia and Ib.” Am J Clin Nutr 20 08;88: 1272–6.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 6 courtesy of Eva’s Supplement Store, NYC.