(Source: Bruce Klemens)

(Source: Bruce Klemens)

Movement disorders and motor programming are all the rage in the physio-world these days and that’s a great thing. We’re stepping back and opening our eyes to the entire body as a system, trying to understand the positions and habits that lead to problems, rather than simply treating the joint as a joint and the muscle as a muscle.

The hip is one of the most powerful joints in your body and as such plays a pivotal role in many athletic movements. Dysfunctions of the hip musculature can rob you of your athletic performance and lead to a vast and painful array of injuries.

The squat is one of the most basic movement patterns of the hip and yet it is often something people struggle to perform with perfect technique. We’re going to take a look at the two most common dysfunctions at the hip, how they affect your squat, and what you can do to fix them.

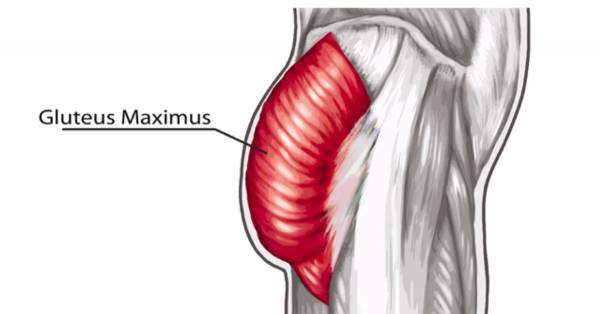

Common Dysfunction #1: Posterior Weakness or Weak Glutes

Of the various issues involved in poor squat technique, poor glute control is easily the largest factor. Movement dysfunction is a game of compensation. When you place a movement demand on your body, it’s going to do its damnedest to perform. If it can’t do so using the correct muscles, then it’s going to start firing all sorts of funky stuff in a mad dash to satisfy your demands.

The gluteus maximus is a primary mover of hip extension. Weak glutes mean weak extension. If this is you, then during the eccentric (lowering) phase of the squat there’s a good chance you’re going to start tipping forward.

People talk a lot about core tightness and abdominal bracing as it relates to the forward lean and that’s absolutely valid – but also secondary. The first step to maintaining an upright torso is proper eccentric glute control.

If you don’t have the glute strength to maintain and drive hip extension, then your lower back will kick in to compensate and guess what? It’s not really suited for the task.

Take a look at an anatomy chart and note the difference in sheer size between your glutes and the musculature of your lower back. Which one would you prefer carry the bulk of that 300lbs you’re trying to squat? If your butt’s weak, your back’s going to hurt – plain and simple.

Another issue with poor gluteal control is the compensations it causes in the anterior hip musculature. When we tip forward during a squat a couple of nasty things happen involving our hip flexors.

First, they will frequently begin to fire in order to help us balance because our glutes aren’t doing the job. Second, and weirdly enough, they will also activate in an attempt to pull us into deeper flexion. In other words, they’re trying to help us squat lower than our gluteal control should allow. The result of this compensation is an over-activation of the anterior hip musculature.

Here’s a basic test for glute max and hip extensor strength:

- Find a table that’s about waist height (a training table would be ideal).

- Stand with your hips directly up against the edge of the table.

- Lean forward so your entire torso is on the table.

- Lift one leg straight back and flex your knee to ninety degrees.

- Without letting your knee drift out to the side or letting your lower back extend (increasing lumbar curvature), lift your foot towards the ceiling. You should feel a tightness in your glutes.

- Now have a buddy try to push down on your thigh with light, but steadily increasing force. If you have weak glutes, it shouldn’t take a huge amount of effort for your buddy to break your hip position.

- If your leg starts to turn or drift sideways or your lower back starts to move, those are compensatory mechanisms and they indicate that your hip extension needs a little tender loving care.

- Do this test on both legs, one at a time.

You can also perform this test without a table by having someone lay prone on a flat surface and having him or her flex the knee and extend the hip the same way. Personally, I prefer the table test because it involves a larger range of motion and therefore provides more information when observed.

Common Dysfunction #2: Anterior Tightness or Tight Flexors

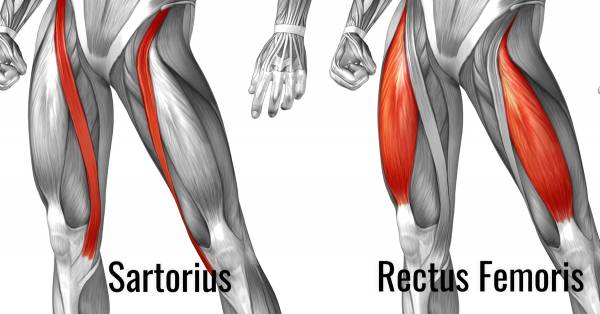

The primary movers in hip flexion are the rectus femoris and sartorius (muscles of the quadriceps; sartorius is pictured right, rectus femoris below) along with the iliopsoas (a deep muscle of the hip). There are a few smaller muscles that also play a role, but typically when you have tight or inflamed hip flexors it’s due to a dysfunction of one or more of these aforementioned muscles.

In a general sense, most hip flexor tightness isn’t the result of activity, but rather the unintended consequence of the passive positions we maintain throughout the day (sitting comes to mind).

While the squat can actually be a profoundly therapeutic exercise in terms of restoring proper gluteal activation and helping mobilize the front of the hips, when done incorrectly it will do the exact opposite: reinforce the negative positions and dangerous compensation patterns.

When your flexors are tight you will have a tendency to lean forward while squatting. A forward lean will shift your center of gravity anteriorly and increase activation of your quadriceps while decreasing activation of your glutes. In addition, once you’re in the bottom position and your hip flexors have turned on, your body is going to want to use your quads to extend your knees, and guess what?

Two of the three main hip flexors are attached to your quadriceps, which are now firing. As a result, when you stand up your flexors are going to stay shortened, which will contribute to an anterior pelvic tilt and make it really difficult to adequately activate the posterior hip muscles.

Another issue with tight hip flexors is that they are usually an indication of missing hip flexion or lacking hip mobility. As I said before, frequently your flexors will turn on as a way of pulling you down into deeper flexion.

But they really shouldn’t have to. Ideally, you should have enough passive flexion to achieve the proper depth without the help of your hip flexors. Tight hip flexors can be both a red flag for missing flexion and a secondary cause for missing flexion. Your body is kind of weird like that.

The easiest test for hip flexor tightness is the Thomas test:

- Lie down supine with your legs hanging off the edge of a table. (Again, a training table would be ideal.)

- Pull your knees to your chest and hold them there with your arms.

- Extend one of your legs while keeping the other held to your chest. Let the extended leg hang off the edge of the table.

- Have a buddy observe the location of your knee (on the extended leg) compared to the position of your hips. Your knee should hang lower than the table. If it is above the table or even in line with it, then this is a positive indication of hip flexor tightness.

Now, let’s fix the problems!

Fixing The Problem

Often when diagnosing a movement disorder you are dealing with a bit of a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma. Was it anterior tightness that caused posterior weakness or vice versa? As with most things, it’s probably a bit of both. What degree of each, though, is unique to each individual.

It’s possible that you started squatting and due to your forty-hour-a-week office posture you already had profound issues with all of the aforementioned problems. It’s just as possible, though, that initially when you started squatting your mechanics were pretty good but you increased the weights too quickly and this got you in the habit of using negative compensations.

Regardless, the most important thing is identifying the existence of the improper movement patterns and addressing them.

Hip Flexion and Hip Mobility Fixes

Quadruped Rocking With Active Shoulder Flexion:

- Get on all fours.

- Push with your arms and drive your hips backwards until yoru hips are sitting on your heels (or as close as you can get, anyway).

- Make sure the motion is coming from your shoulders rather than your hips.

This drill is basically a physiological trick to get your body to move into a position of deep flexion without activating your flexors. If you get on all fours and simply start shifting backwards, then its pretty likely you’re going to engage your flexors to do so.

By focusing on pushing with your shoulders, you’re using different muscles to produce the movement and that will allow you to achieve the position without activating your flexors. This will also teach your body that your hip flexors don’t need to be firing as hard as possible in order to achieve this position at the hip.

Thomas Stretch:

Same thing as the Thomas test described above, but this time rather than simply observing the position of the thigh, have your buddy gently press your thigh downwards until you feel a stretch through your quad and the front of your hip. Hold this stretch for thirty seconds to a minute, and do this two or three times.

I’m not crazy about a lot of other hip flexor stretches because most of them involve you being upright. As long as you’re upright and having trouble balancing, then your hip flexors are probably going to fire. In other words, if you already have this dysfunction then your flexors are already prone to over-activation. Stretching them in an upright position will turn them on to a degree, but what you’re attempting to accomplish is getting them to shut off. See the problem?

Paleolithic Chair:

I think the most profound stretch or mobilization for overall hip flexibility is the Paleolithic chair. Get down as low as you can while keeping your heels on the ground and hang out there. If you have to grab onto something to maintain balance at first, that’s fine – just focus on getting low and keeping your heels on the floor. Try to do this for three to five minutes at a time initially. Ideally, you will build up to a total of about ten minutes a day.

Posterior Strength and Gluteal Activation Drills

The best way to get your glutes firing during a squat is to do some basic warm-up drills that will reinforce firing your glutes. One of my favorite progressions is as follows:

- Glute Bridge – 10x (both legs)

- Single Leg Glute Bridge – 10x each leg

- Fire Hydrants – 10x each leg

- Quadruped bent-knee hip extension – 10x each leg

You can perform all of these fixes as a five to ten minute mobility and warm-up session before you squat, which should significantly improve your squat positioning. But really, the simplest fix for weak eccentric glute control is also one of the most straightforward: lighten your weights and focus on the eccentric portion of the squat with specific attention to keeping your torso upright.

Mindfulness of your movements and strict adherence to proper patterns is the best medicine for your ailments.