Kids are just smaller, slightly weaker adults, right? They’d be fine with the same program you’d give any twenty-something-year-old, wouldn’t they? If worse comes to worst, drop a set off, reduce the reps, or maybe adjust the intensity a little bit, right?

Kids are just smaller, slightly weaker adults, right? They’d be fine with the same program you’d give any twenty-something-year-old, wouldn’t they? If worse comes to worst, drop a set off, reduce the reps, or maybe adjust the intensity a little bit, right?

Those are all-too-common to hear comments that are actually just plain wrong. It is true that children and adults share a number of factors in common. Physiologically, they are both made up of bone and muscle tissues, they have the same organs, and they need the same fuels. So, why is it you can’t train them both the same way?

Lets refer back to the article I wrote on kids and weightlifting for a split second. You will notice in that article that I put an emphasis on making activities fun for kids. Children like to play games, and they don’t like to stand still for too long.

Psychologically, there is a huge difference in attention and focus between a child and an adult.

It is fair to say that there is a crossover somewhere in the middle as the child matures, where a child actually demonstrates and wants to focus on a particular sport. However, you must still use caution when programming for kids. So without specifically delving into weightlifting just yet, let’s view methods currently being used for developing youths.

Introducing the LTAD Method

The Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) method was originally created by Istvan Balyi. It is a program or template for developing youths through to adulthood with safe and efficient training strategies.

The idea behind the model is that there are optimal windows of opportunity during the development of youths to advance certain physiological characteristics.1

After its initial development, the model was later criticized by a number of researchers for various issues, but it has since been used and is now continually viewed as an essential guideline for developing youth.2 Other options evolved to follow, such as the Youth Physical Development (YPD) model by Lloyd and Oliver.3

The purpose of these models is to bring attention to the fact that as a child grows, there are a number of physiological adaptions happening.

It is critical that fundamental movement skills, or movement literacy, are attained during these stages. As the child goes through adolescence, he or she will mature psychologically and likely look to specialize in a set sport.

Weightlifting Development

I would love to tell you an age where all kids can start lifting, but simply put, there is no such thing.

As stated previously, it all comes back to the psychological status of the children. Do they want to focus and engage? Can you get them to listen and focus? If you can’t, don’t panic – in time, it will happen.

An interesting fact to note: It has been proven that late maturers may actually develop into better athletes than their counterparts in various sports.4 So don’t disregard the kids that can’t yet engage or focus your attention towards the earlier-maturing kids – you never know how they all might develop!

How to Teach Little Johnny Weightlifting

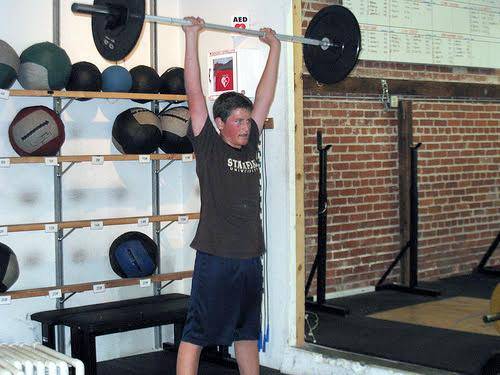

So, here you have little Johnny. He may be somewhere between the ages of ten and fourteen. He has decided he wants to start learning weightlifting. Fantastic news, right? So what are you going to do?

As stated above, we now know you can’t just give Johnny a program that your older guys do – you’ll just end up breaking him.

Weightlifting is a highly technical sport, and although some say this can be a hindrance, it can also be a blessing. You have bought yourself a period of time where you can perfect the technique without little-to-no loading.

At my gym, we are fortunate enough to have bars available that weigh 5kg and bumpers that are 1kg each, as well. Please don’t think that I am against loading up a child with weights, but you should take it as a gradual process – there is no need to rush things.

Now, referring back to our LTAD and YPD models, it has been stated that strength gains are typically greatest after a growth spurt. This is easiest to understand with males, as testosterone levels dramatically increase at these points.

So although it is good to start strength development early, due to hormonal status of the children, this pre-growth spurt period gives an optimal opportunity to focus attention on technique. You can then develop strength later, in a period proven to be most efficient for youths.

Here in the United Kingdom, we have competitions for U11 and U13 that are scored on technical execution of the lifts. This further demonstrates that technical mastery is an essential component to lifting and should be viewed as the more important element for kids.

The Soviet lifting manuals that are easily available nowadays also state clearly that class-three lifters (the newbies) must spend up to a year developing the technique of the lifts.

Why is this? Well, one way to view it is fairly simple and logical. You need to learn how to ride a bike before you can ride a bike really fast.

If you can make the movements of the lifts second nature, then adding loads will be the simple progression. Additionally, it will be a lot easier to focus on strength without the concern of “forgetting” how to lift.

So, don’t get carried away trying to make your lifters super strong straight away. With a bit of organization and planning, you can get the most out of your lifters. Emphasize technique to begin with, and make the shift to strength as your lifter attains mastery for the lifts.

Don’t rush – you and each child have a whole lifetime ahead of you!

References:

1. Balyi, I., Sport System Building and Long-term Athlete Development in British Columbia. (2001) Canada; Sports Med BC.

2. Ford, P. Croix, M. Lloyd, R. Meyers, R. Moosavi, M. Oliver, J. Till, K & Williams, C., “The Long-Term Athlete Development model: Physiological evidence and application.” Journal of Sports Sciences, (2011) 29, 389-402.

3. Lloyd, R. & Oiver, J., “The Youth Physical Development Model: A New Approach to Long-Term Athletic Development.” Strength & Conditioning Journal, (2012) 34, 61-72.

4. Lloyd, R. & Oliver, J., Strength & Conditioning for Young Athletes. (2014) Oxon, UK: Routeledge.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 by Londonyouthgames (Own work) [CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 courtesy of CrossFit LA.