In part one Historical Perspectives I raised the two challenges I faced in the 1980s – first, that there were inadequate numbers of exercises being used in single-leg format, and second, that the few exercises being used were predominantly quad dominant.

All parts of these series:

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 1: Historical Perspectives

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 2: Challenging The Overreaction

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 3: 7 Key Practical Strategies

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 4: Correcting The Imbalances – You are here

The Final Words on Single-Leg Exercise

Thirty years later, the challenges I believe exist for the optimal application of single-leg exercises are these:

- Too many single leg exercises

- An imbalance of quad dominant to hip dominant exercises

In essence, the first problem was solved and then moved into an overreaction that created new problems, while the second problem still exists. I believe the second point is currently the greatest challenge moving forward. This flaw in program design and training – dominating in quad dominant exercise – presents far greater risks and damage than the first concern.

I have shared this message in writing consistently since the 1990s:

It is my belief that an imbalance between quad dominant and hip dominant exercises where quad dominance is superior results in a significantly higher incidence of injury and detraction from performance.1

Why the Limitations in Program Design Have Not Advanced

I suggest that program design, at least at the mainstream level, has not advanced in this area of muscle imbalance during the last few decades. For example, I present a program from a mainstream popular U.S. bodybuilding magazine from 1997, which was indicative of the dominant trends at the time, written by people I describe as trend followers. An analysis of this program reveals the following:2

Analysis by muscle groups/lines of movements in strength training workouts in Stage 1:

I challenge you to obtain any dominant paradigm-based program from today and run this analysis. I suggest that for the majority of cases, you will see similar levels of sequencing imbalance as appeared in the above bodybuilding magazine.

The fact that the world of training has failed to adequately address this speaks to the absence of true understating of my concepts, in particular by those who have chosen to publish my concepts unreferenced and without adequate understanding of their intent.

A Crash Course in My Teaching on Prioritization

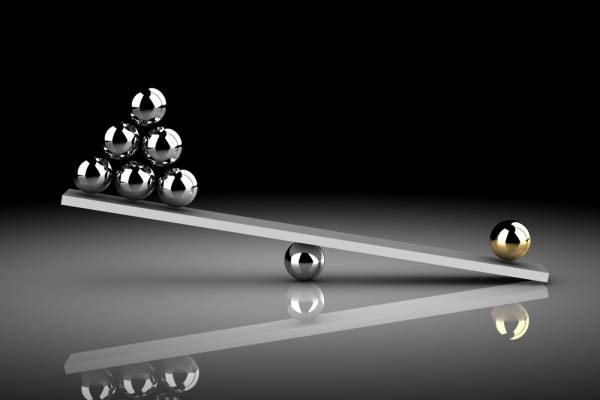

The key to long-term health in training is balance in program design:

Balance: all things being equal, and independent of any specificity demands, the selection of exercises should show balance throughout the body. For example for every upper body exercise there would be a lower body exercise. For every upper body pushing movement, there would be an upper body pulling movement. For every vertical pushing movement there would be a vertical pulling movement. For every hip dominant exercise there would be a quad dominant exercise. And so on.3

The challenge prior to my publications in the late 1990s was that no one knew how to create balance in program design. I identified three keys to balance in program design – sequence, volume, and intensity:

You see, in essence all programs have an imbalance or a prioritization. This come from the sequence of exercises within the workout and week, the allocation of volume, the relative use of intensity, the comparative selection of exercise categories and so on.4

The simplest way to start out ensuring balance in your programs is to being with an understanding of the role of sequence.

The Role of Sequence in Prioritization

Prioritization by sequence means that a muscle group receives priority and benefit by being placed early in the training program. Prioritization by sequence can occur in two ways:

- Within the workout: The higher an exercise is placed in the daily workout, the greater the priority and benefit received by that muscle group. The number one way to give a muscle group priority is to place it first in the workout.

- Within the training week: A muscle group that is trained early in the training week or microcycle will receive priority and the associated benefits in comparison to a muscle group trained later in the week. The most effective way to prioritize a muscle group is to train it early in the training week or microcycle.5

In conjunction with my prioritization, balance, and lines of movement concept, I have developed and taught a technique where you can analyze any strength-training program for its balance. You can learn more about this in my live presentations from 1998 onward, but here’s an extract:

Let’s do the lower body. You know how I divide the lower body? Hip dominant and quad dominant. You know why? Quad dominance anteriorly rotates the pelvis; hip dominance posteriorly rotates the pelvis. You want to create balance around the pelvis, you need guess what? Equal attention, by volume and sequence.

So QD vs. HD, lets count them (counting). 4:1 (day 1) and 4:1 (day 2) again. We call push press a quad, because it’s a vertical trunk. We have got a ratio of volume of 4: 1. That imbalance is actually even worse than the one above. The only safing is that there is more overlap between HD and QD; they do use more similar muscle. Having said that, it’s still an incredible blow out on ratio. So that is volume.

Now let’s look at sequencing. You’d imagine it would reverse the sequence, wouldn’t you? QD and HD, like one day that comes first, and you swap it over. What comes first (day1)? Quad. What comes first (day2)? Quad. Where is HD? Last and nearly last. So by sequencing also you are creating hip suicide, absolute hip suicide. And guess what’s going to happen? When the pelvis is rotated resulted by these activities and the nerves are getting impinged, what you going to get? Hamstrings strains, quad strains, hamstring tears, groin strains, groin tears, lower back pain… you destroy the health of the lower body of the athlete. Of course when the pelvis is rotated forward it changes the position of the whole spine, changes the way you run, changes the power output in the lower body, changes the muscle tension, affects the ability to recover.

Now remember: ideally you’d reverse it over so it was QD and HD and it would be HD and QD. But still whatever happens on the first day of the week is still getting a better result, so you need to put the weakness prioritized on the first day. If you would assume, as generalization, where would people mostly be weak? HD or QD? HD. especially Shawn in this situation. So Shawn would go HD-QD, QD-HD. at the very worst. More ideally he’d go HD-QD and HD-QD again.

You don’t have one program. His initial program might be hip – quad, hip – quad. I’ll show you the progression. If I was to reverse this program, the downsides of this program, this is what I’d do with Shawn. We got an A, B, C and D day. His first program would be HD – QD on both days. His next program, his next stage, I might allow a reversal for variety, and down the track he might even come back to QD-HD, HD-Qd. that’s 3 distinct alternatives that he’s got. But believe me: he’d spend a lot of time in the first one to counter that. If he did this (old) program for 6 month, guess what? He’d have to do the other program for 6 month to counter it. Now you understand how I design programs a little bit better? You reverse the imbalances that they’ve been exposed to.

The bottom line is: for some reason people in this industry believe that sequencing is locked in, that there is only one way to sequence.

…So even if you had equal volume, and had equal prioritization, if the loading exposure was different push and pull, you’d still have an issue.6

The Lines of Movement Concept

During the 1980s, I began to research methods of categorizing strength exercises. By the end of this decade I had developed a concept I called lines of movement. After trialling this method for about ten years, I released details of this and other methods I developed for categorizing exercises. I structure this organization under the umbrella concept of family trees of exercises. I then expand into lines of movement, and then divide exercises based on the number of limbs and joints involved.

These methods go far beyond simple organization. They allowed me to develop my methods of analyzing balance in strength training program design. I believe these innovations are the most effective tools available to guide a person designing a program to create optimal balance and reduce injury potential.

The first time I expanded fully on this concept was in a 1998 seminar:7

After many years I have decided that there [are] two family trees in lower body exercises – one where the quad dominates, and one where the hip dominates. When I say hip I mean the posterior chain muscle groups – the hip extensors; which are gluteals, hamstrings, lower back – they’re your hip extensors. And I believe this – the head of the family in the quad dominant exercises is the squat. That’s the head of the family. And there are 101 lead-up exercises to it and there’s a few on after it as well. But the core exercise for the quad dominant group is the squat. It’s the most likely used exercise in that group for the majority of people.

The hip dominant exercises – the father of the hip dominant tree is the deadlift – which when done correctly would be the most common exercise of that group. There are lead-in exercises, and there are advanced exercises from it.

So I build my family tree around the squat and I build my family tree around the deadlift. And I balance them up. In general, for every squat exercise or every quad dominant exercise I show in that week a hip dominant exercise in that week. And what do most people do in their program designs – they would do two quad dominant exercises for every hip dominant exercise. What is the most common imbalance that occurs in the lower body?

….To balance the athlete I work on a ratio of 1 to 1 of hip and quad dominant – in general. And I can assure you – most programs you’ll see are 2 to 1 – quad and hip.

That’s a concept I’m sure you’ll have never heard before because this is the first time I have spoken about it.

The following shows a breakdown of the body into major muscle groups/lines of movement, and then into examples of exercises. It is what I call ‘the family trees of exercise’. Use this to assess balance in your exercise selection.

Now I am going to show you how I break the muscle groups up:

Lower body:

- Quad dominant

- Hip dominant

Upper body:

- Horizontal plane push

- Horizontal plane pull

- Vertical plane push

- Vertical plane pull

These concepts are now used throughout the world. They are unique concepts aimed at solving a real problem. However, they are not being used appropriately or effectively, and therefore the problem I described in the 1990s not only exists, but I suggest it has become a bigger problem.

I suggest that ethical and well-read authors and presenters reference and credit the origin. The proliferation of unreferenced publishing of this concept has meant that the world has been denied a fuller understanding of the intent of this concept.

The Definition of Quad and Hip Dominant Movement

One of the missing parts is a clear understanding of how I defined and differentiated between a quad dominant and hip dominant exercise. The lower body was more complicated than the upper body, and required significantly more deliberation. In essence, the categories I ultimately identified (quad and hip), both work through similar lines of movement and use similar muscles (in multi-joint movements at least).

The real separation between the two groups (quad and hip) when performing multi-joint movements is how much quad is being used versus how much of the posterior chain muscle groups are being used.

This dilemma was shared in print in my earlier writings:8

Attempts to isolate the quad dominant from hip dominant exercises.

The majority of lower body exercises will have some overlap between the typical quad dominant and hip dominant exercises. Take the squat (quad dominant) and the deadlift (head of hip dominant family tree). They both involve all the muscles of the legs, hips and lower back. The subtle differences are poorly recognized however, which is why, in my opinion, most coaches cannot see imbalances in training that they don’t understand. The muscle groups used in the squat and deadlift may be similar but the training effects are significantly different!

This was my thinking – to simply create a definition that separated these two relatively close and overlapping movements. So my definition of what constitutes a quad dominant and what constitutes a hip dominant movement was outlined in the following way:9

As a guide, I categorize a multi-joint lower body exercise as hip dominant if it has a significant degree of trunk flexion (placing the gluts on stretch) e.g. hip break lower bar squat, deadlift. If it involves a vertical or near-vertical trunk (e.g. lunge, knee-break squat), I categorize it as a quad dominant exercise.

Here’s another explanation:10

I will go over how I categorize exercises into each of these two groups. Please work with me on this, however – it is a loose, practical definition – not an exact science…

Any lower body exercise where the trunk remains at or above 45 degrees of flexion I loosely call a quad dominant exercise e.g. Squat. Any leg exercise where the trunk is flexed greater than 45 degrees I loosely call a hip dominant exercise.

So a lunge is a quad dominant and a leg press a quad dominant – the later dependant upon the back support angle, but for all purposes of this working definition, a quad dominant exercise.

As you can see statements above, made over a decade ago, despite my generalization that the squat is the head of the quad dominant tree and the deadlift is head of the hip dominant tree, which category any given exercise is placed depends on how that exercise is conducted.

The Risks of Prioritization of Quad Dominant Movements

Now you have a clearer understanding of the history and intent of the line of movement exercise categorization concept, as well as how to determine which of these two categories any given leg exercises falls into. So, I want to stress upon you the risks you are taking by ignoring this guidance. The implications of creating muscle imbalances through prioritization of quad dominant movements occur in this sequence:

Stage 1: An initial feeling of superior benefit, in leg strength and or ability to leg drive.

Stage 2: A cessation of benefits, in particular transfer to sport or your specific function, despite increased gains in the quad dominant movements.

Stage 3: Performance decrement due to adaptation to non-specific leg strengths that don’t transfer and delayed ground contact time from adapting to long, slow lifts.

Stage 4: Neural inhibition impeding strength expression and providing warning signs of developing issues – typically referred pain into the lower extremities (e.g. muscle strains of the upper or lower legs and or groin), but can be as high as the lower trunk (e.g. hernia like symptoms).

Stage 5: Higher-level injuries such as ligament ruptures, joint dislocations, and muscle tears, causing a permanent negative impact on your function, appearance, and quality of life. I suggest that by this stage the time frame to joint replacement (hip and knee) has been brought forward five to twenty years.

Sounds dramatic? No drama intended. Simply my conclusions from thirty-plus years of studying human response to intense and long term training loads. I suggest we have more athletes and non-athletes entering stage five of this progression in the world than ever before in the recorded history of mankind. This may be simply my hypothesis and theories, but I will be willing to learn from any of you who have ignored my advice in the decades to come.

Quad Dominant Athletes Should Not Be Given Quad Dominant Training

For those who are participating in competitive sports or training athletes who are, I take this moment to share this point. If the sport is a quad dominant sport (and most are) you should not be allowing the athlete to do any quad dominant exercises until you are sure that the muscle balance between quad and hip dominance has been restored to a satisfactory level.

What is satisfactory? It’s unlikely you will be able to assess optimal transfer, as this is a high-level coaching concept possessed by few. Unfortunately for most strength coaches, the presence of any lower body injury (chronic or impact) should raise doubts in your mind as to whether you got this balance right.

Yes, this approach is counter to the sport specific paradigm, which is in my opinion synonymous with the functional training dogma – i.e. we know what exercises will transfer. (In fact you don’t, until you do them, and only if you have the ability to assess transfer, which I suggest few possess. After all, no one teaches it. You won’t learn it in formal sport science education, and the people most are drawn to because of their marketing prowess have no chance of being able to teach this.)

There is no shortage of books on functional training by authors who have successfully promoted their expertise, in which you are encouraged to imitate the sporting movement. I strongly suggest you disregard this advice.

Close-Kinetic Chain Exercises Exacerbate This Imbalance

One of the many dominant trends that is of dubious value at best is the dogma that exercises are more functional if done standing up. I suggest those who promote this concept lack the experience in coaching to fully appreciate this area of knowledge, and those who blindly copy this lack the desire or ability to apply objective thinking.

In short, one of the implications is that more exercises are being done in a position that increases the quad dominant component. For example, for all the time spend standing shaking a heavy rope that has more application on a shipyard dock than in a physical training program, are you in a hip dominant position for similar durations and similar intensity in leg contractions? I doubt it.

You Are Wrecking Your Future

Quite simply, following the quad dominant trends in popular training programs and training methods is resulting in a whole wave of humans reducing their performance potential in the mid-term and reducing the quality of their lives in the long term.

I understand that my assessment of the current situation and my solutions will be considered heretical, as was the response to many of my significant teachings when first released – the concept of using digits to time strength movements; the suggestion that the pause between the concentric and eccentric in strength training was a variable worthy of measuring and manipulating; the concept of lines of movement, and associated suggestions such as doing chin ups is not equal to and fails to counter the bench press; the suggestion of control drills before training – I could go on.

What I have learned is that the most vicious reactions come from those whose guru status is being threatened because my teachings appear to undermine them. What I have also learned is these same protagonists turn around within a few years and teach my concepts, albeit as their own.

What I suggest you do is not wait until your guru has overcome his or her hurt and finally brought to the market the ideas I have proposed in this article series. What I suggest is you use these ideas immediately, giving you the greatest chance to overcome, reverse, and essentially salvage your body before too much more damage is done.

All parts of these series:

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 1: Historical Perspectives

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 2: Challenging The Overreaction

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 3: 7 Key Practical Strategies

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 4: Correcting The Imbalances – You are here

References:

1. King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises(book), p. 99

2. King, I., 1998, Strength Specialization Series DVD/Audio, King Sports International, Brisbane AUS. Content that changed the way the world did strength training.

3. King, I., 1998, How to Write Strength Training Programs (book), p. 38

4. King, I., 2003, Ask the master, p. 143

5. King, I., 1998, How to Write Strength Training Programs, p. 85

6. King, I., 2000, Injury Prevention & Rehabilitation (DVD)

7. King, I., 1998, Strength Specialization Series (DVD), Disc 3, approx 1hr 03m 00sec in.

8. King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises p. 99

9. King, I., 2000, How to Teach Strength Training Exercises (2000), p. 106

10. King, I., 2003, Ask the Master, (book), p. 18

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.