The fear of dietary fat—butter, oil, meat, etc.—is a recent phenomenon. Only during the past several decades have we become fat-phobic. Fat has 9 calories per gram, compared to just 4 calories per gram for protein or carbohydrates. These basic facts, when considered superficially, underlie the myth that “eating fat makes you fat.”

The fear of dietary fat—butter, oil, meat, etc.—is a recent phenomenon. Only during the past several decades have we become fat-phobic. Fat has 9 calories per gram, compared to just 4 calories per gram for protein or carbohydrates. These basic facts, when considered superficially, underlie the myth that “eating fat makes you fat.”

During the 1970’s, most health-related institutions began embracing the US government’s low-fat dietary guidelines. The public largely followed suit, accepting the guidelines at face value and striving to implement them. We now have decades of data with which to critique these guidelines and we can conclude, quite objectively, that they have failed.

The following is a brief overview of what has transpired, with respect to fat consumption in the US, since the 1970’s:1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

- Total fat consumption has decreased.

- Saturated fat consumption has decreased.

- Animal fat consumption has decreased.

- Omega-6 fat consumption has increased.

- Seed oil consumption has increased.

- Obesity has increased.

- Type-2 diabetes prevalence has increased.

- Heart disease mortality has decreased, but the prevalence of heart disease remains very high.

Guidelines at Odds With History

The guidelines were supposed to prevent weight gain, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic, degenerative diseases. Instead, the opposite happened, but why?

The US dietary guidelines contradicted, sometimes in radical ways, traditional human diets, including those as recent as our pre-Industrial Revolution ancestors. Specifically, the guidelines promote low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets, whereas ancestral diets were lower in carbs and higher in fat and protein.

Diets during the Paleolithic era varied greatly, because geographic variance made different foods available to different groups. This being said, we can make some generalizations about what our ancestors ate.

For example, nearly three-fourths of hunter-gatherer societies derived at least 50% of their calories from animal foods.7 Practically speaking, this means more fat, more protein, and less carbs. Anthropologists estimate the following macronutrient ratios for hunter-gatherers societies:7, 8

- Fat: 20 to 40% of total calories

- Protein: 25 to 35% of total calories

- Carbohydrates: 25 to 40% of total calories

In the US, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), carbohydrate intake accounts for approximately 50% of total calories for adults; protein accounts 16%, while fat accounts for the remaining 34%.9

As you can see, compared to our ancestors, we eat more carbs and less protein, but our fat intake is comparable. Unfortunately, the types of fat most people eat today have changed considerably.

Will the Real Bad Fat Please Step Forward?

During the past half-century, health authorities encouraged replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat. The former was deemed “bad fat,” whereas the latter was called “good fat” or “heart-healthy” fat.

To understand the consequences of this misguided advice, we need to review and summarize the various types of fat.

- Fatty acids (fat) consist of chains of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms attached. Saturated fatty acids have the maximum number of hydrogen atoms attached to each carbon atom. Unsaturated fatty acids have carbon atoms without attached hydrogen atoms.

- There are two types of unsaturated fat—monounsaturated and polyunsaturated.

- Furthermore, there are two primary types of polyunsaturated fat—omega 6 and omega 3.

We were told that unsaturated fat is healthy, but this isn’t necessarily the case. As it turns out, instead of worrying about saturated fat, we should have been far more wary of omega-6.

Our Ancestors Ate Seeds, but Not Seed Oils

The US dietary guidelines still push polyunsaturated fat, but fail to adequately differentiate between omega-6 and omega-3. As a matter of accuracy, we can’t say that either omega-6 or omega-3 is “bad.”

In fact, both are known as essential fatty acids (EFAs) because the body requires them and can only get them from food. On the other hand, omega-6 causes big problems when we eat too much of it; and that’s exactly what has happened since the 1970’s.

The main culprits have been seed oils, a category of food that is relatively new to the human diet. Seed oils include:

- Corn oil

- Soybean oil

- Sunflower oil

- Canola oil

- Safflower oil

- Grapeseed oil

- Cottonseed oil

The reason our ancestors never consumed seed oils is because extracting oil from these seeds requires special processing technologies, including high heat and hexane solvents. In other words, they avoided the problems associated with high omega-6 consumption by default, because they didn’t have access to omega-6-rich foods, like seed oils.

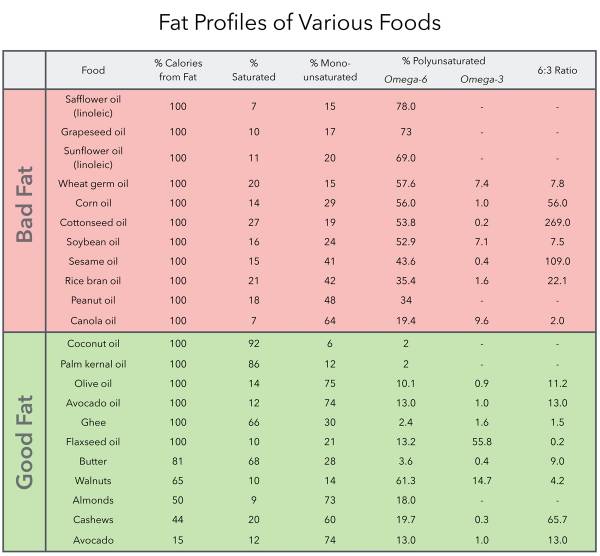

Every source of fat has its own unique distribution of fatty acids. As seen in the chart below, seed oils are disproportionately rich in omega-6. None of our traditional sources of fat even come close. Our ancestors certainly consumed omega-6—from eggs, nuts, seeds, poultry, and other whole food sources—but not in the quantities consumed today.

From 1909 to 1999, for example, consumption of soybean oil in the US increased more than a thousand-fold, from 0.006% to 7.38% of calories, on average. During the same period, total omega-6 consumption increased from 2.79% to 7.21% of calories, while the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 increased from 5.4/1 to 9.1/1.10

As discussed below, the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio is extremely important; higher ratios cause many problems. During the Paleolithic era, this ratio was very low (approximately 1/1), whereas today, ratios approaching 17/1 are common for Western diets.8, 11, 12

Why the Omega-6 to Omega-3 Ratio Matters

Omega-3 is one of the body’s most important nutrients. Some of its many beneficial properties include:

- Reduced inflammation13

- Improved risk factors for cardiovascular disease14

- Improved the quality of the skin15

- Improved brain health, especially during the developmental years16, 17

If we consume proportionally too much omega-6, we cannot effectively metabolize the omega-3 we consume. This is because omega-6 and omega-3 compete for the same enzymes, which break them down into components the body assimilates.18

In other words, you won’t necessarily reap the benefits of increased omega-3 consumption unless you simultaneously decrease your omega-6.

The Omega-6 Problem

We were told that saturated fat was the enemy. We were told to replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat—primarily omega-6-rich seed oils. Doing so, however, has only exacerbated our health problems.

In 2010, the British Journal of Nutrition published a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving the replacement of saturated fat with omega-6 polyunsaturated fat. Doing so, the study demonstrated, actually increases all-cause mortality.19 A similar study, published in 2013, corroborated these results.20

Despite the mainstream view that omega-6 is healthy, there are many reasons to conclude the opposite. Limited consumption of omega-6, as per our ancestors (less than 3% of total calories) is ideal, but modern consumption levels have many consequences, including the following.21, 22, 23, 24, 25

- Immune system repression

- Lowering of healthy HDL cholesterol

- Increased risk of heart disease

- The susceptibility of omega-6 to oxidize, which promotes free radical damage

- Increased risk of prostate cancer

- Increased risk of breast cancer

Practical Advice: Learning From Our Ancestors

Everyone knows there is “good fat” and “bad fat.” Saturated fat, however, isn’t the nutritional menace it’s been portrayed as.

That role should go to seed oils, based on their excessive omega-6 quantities. The US dietary guidelines have many flaws, especially with respect to fat. The following guidelines, though greatly simplified, are more aligned with ancestral diets as well as contemporary nutrition science:

- Instead of focusing on reduced fat, focus on reduced carbs.

- Eat mostly monounsaturated and saturated fat (all types of animal fat, avocado, coconut, olive oil, whole nuts).

- Minimize omega-6 by eliminating seed oils (flax oil is okay).

- Ensure optimal omega-3 by eating oily fish (sardines, tuna, salmon, etc.) and/or taking an omega-3 supplement.

References:

1. Kearney, J. “Food consumption trends and drivers.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365 (2010): 2793–2807. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0149

2. Wright, JD et al. “Trends in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients — United States, 1971—2000.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 53 (204): 80-82.

3. Ford, ES et al. “Trends in energy intake among adults in the United States: findings from NHANES.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 97 (2013): 848-853. doi: 10.3945

4. Flegal, KM et al. “Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among us adults, 1999-2010.” JAMA 307 (2012): 491-497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39

5. Menke, A et al. “Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the united states, 1988-2012.” JAMA 314 (2015): 1021-1029. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10029

6. Mozaffarian, D et al. “Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update.” Circulation 133 (2016): e38-360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

7. Cordain, L et al. “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71 (2000): 682-92.

8. Kuipers, RS et al. “Estimated macronutrient and fatty acid intakes from an East African Paleolithic diet.” British Journal of Nutrition 104 (2010): 1666-87. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002679

9. Wright, JD et al. “Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients in adults from 1999–2000 through 2007–2008.” US Department of Health and Human Services. NCHS Data Brief 49 (2010): 1-8.

10. Blasbalg, TL et al. “Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 93 (2011): 950–962. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643

11. Simopoulos, AP. “The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 56 (2002): 365-79.

12. Kris-Etherton, PM et al. “Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the United States.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71 (2000): 179S-88S.

13. Kiecolt-Glaser, JK et al. “Omega-3 supplementation lowers inflammation and anxiety in medical students: a randomized controlled trial.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 25 (2011): 1725-34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.229

14. Mozaffarian, D et al. “Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 58 (2011): 2047-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063

15. Spencer, EH et al. “Diet and acne: a review of the evidence.” International Journal of Dermatology 48 (2009): 339-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04002.x

16. Judge, MP et al. “Maternal consumption of a docosahexaenoic acid-containing functional food during pregnancy: benefit for infant performance on problem-solving but not on recognition memory tasks at age 9 mo.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 85 (2007): 1572-7.

17. Singh, M et al. “Essential fatty acids, DHA and human brain.” Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 72 (2005): 239-42.

18. Simopoulos, AP et al. “An increase in the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity.” Nutrients 8 (2016): 128. doi: 10.3390/nu8030128

19. Ramsden, CE et al. “n-6 Fatty acid-specific and mixed polyunsaturate dietary interventions have different effects on CHD risk: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” British Journal of Nutrition 104 (2010): 1586-600. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004010

20. Ramsden, CE et al. “Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis.” British Medical Journal 346 (2013): e8707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8707

21. Lands, WE. “Dietary fat and health: the evidence and the politics of prevention: careful use of dietary fats can improve life and prevent disease.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1055 (2005): 179-92.

22. Okuyama, H et al. “ω3 fatty acids effectively prevent coronary heart disease and other late-onset diseases: the excessive linoleic acid syndrome.” World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics 96 (2007): 83-103. doi: 10.1159/000097809

23. Hibbeln, JR et al. “Healthy intakes of n−3 and n−6 fatty acids: estimations considering worldwide diversity.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 83 (2006): S1483-S1493.

24. Williams, CD et al. “A high ratio of dietary n-6/n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with increased risk of prostate cancer.” Nutrition Research 31 (2011): 1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.01.002

25. Murff, HJ et al. “Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in Chinese women: a prospective cohort study.” International Journal of Cancer 128 (2011): 1434-41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25703