Click Here for Wil’s Free Stronger Than Ever Weightlifting Program

In the past, I have just given the advice to “brace the core.” This cue brings about the image, or it should at least, of bracing your abdomen for a punch to the gut from Chuck Liddell. (There are probably more current references, but the Iceman packed a punch back in the day.)

The brace is still important, but it isn’t the only piece of the puzzle to creating a trunk that is stable enough to stand up with massive weights on the chest or overhead. The breath is the second piece of that puzzle, and without the correct breath, no one can brace in the right way.

What Is the Core?

Before we get to the breathing part, I think a definition of the core is important. In terms of weightlifting the core is anything that is part of your trunk, including but not limited to:

- Rectus abdominus

- Internal and external obliques

- Transverse abdominus

- Spinal erectors

- Deep hip flexors

- Pelvic floor

- Diaphragm (pay attention to this one)

I would go so far as to say that anything that crosses into these muscular groups, like your lats sharing vertebrae with the erectors, could be included in your core. If we want to go even a step further, muscles above and below have a direct relationship to the proper function of the core too – as in the gluteals playing a big role in the ability of your rectus abdominus to function well. So your “core” includes a lot of stuff.

The Importance of Bracing in Weightlifting

Bracing is simply the best way to engage the entirety of the core and to create stiffness in an area that normally does not have stiffness. Mike Robertson, coach at Indianapolis Fitness and Sports Training, defined the function of the core in the simplest way that I have heard, when he talked about “the two Rs” of the core.

The core has two functions: The first is redistribution, as in redistribution of tension. Think of this R like a suspension bridge. The cables themselves are not tight to begin with, but they can support the weight of the bridge below through a redistribution of tension, like in a plank. The second R is redirection, as in the redirection of force. Power that is created in the lower body can only be moved along the kinetic chain through a core that is tight.

In Olympic lifting, we must use the core with both Rs in mind. The first is redistribution of tension, as the initial lift off from the ground needs a tight system to budge the object at rest (the barbell on the floor). Once the second pull is initiated, a redirection of force is necessary to finish the pull and begin to move under the bar.

Bracing your core is the only way to create enough tension so that your core does not fold under loads. The alternatives to bracing are twofold. First, you can use an overly extended posture, in which you are relying solely on tension in the lower back spinal erectors to maintain position. The second option is to hollow the abdominal cavity, as in the bodybuilding “abs” pose (please excuse me if I am not up to date on my bodybuilding lingo). While the abs certainly pop, and the pecs look large in this pose, it is not creating the high-tension system that we need for weightlifting. The only true way to get your core into the action is to brace your core, and the only way to effectively brace your core is to breath your way to it.

Bracing Through Breathing

Bracing the core through breathing is easily seen in powerlifting where almost every single athlete is using a belt. With the belt on, it is not uncommon to see a powerlifter push their belly out over the top and bottom of the belt. If you know some powerlifters, you might think this is due more to their diet choices rather than their mastery of core control, but with 1000lbs on their backs or 800 on the floor, they are likely in control of exactly the kind of posture that’s wanted.

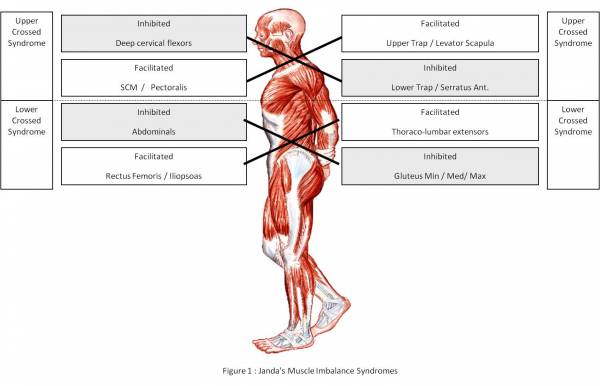

Bracing is about filling your trunk with pressure and this is exactly where your diaphragm comes into play. Most athletes I run into are in an extended posture, as in an accentuated lordosis of the lumbar spine, anterior tilt of the pelvis, and flared lower ribs. This posture is also known as Janda’s lower cross syndrome, characterized by muscles that are overly tonic or phasic (tight hip flexors and erectors, weak gluteals and abdominals) The simple nature of this extension posture generally means that the diaphragm is inhibited.

Ideally the core is a cylinder, like a can filled with your favorite (highly) processed food. If you imagine that same can slightly crushed on the back side and bulging out the front side, you would picture a can that is ready to burst – one that has a weakness because disproportionate pressure is being exerted on one side. An extension posture is this badly misshapen can. This posture means that the top of your core (your diaphgram) is not facing the bottom of your core (the pelvic floor) and creating pressure in the core is much more difficult to do now.

To effectively Olympic lift, you must use a bracing posture. Try doing this now, first by tightening your stomach for the knockout blow, and then breathing into your stomach. With the diaphragm acting as part of the equation you now have a complete brace.

This is easily illustrated without a lifting belt by placing your hands on your obliques right above the crest of the pelvis. When you brace properly, you will see your hands move laterally. Now put one hand on your stomach, breathe deeply into your stomach. You will feel your hand move, and your ribs should expand laterally, as well. We call this “breathing into the brace.” Complete this move before every snatch, clean, jerk, or squat.

Click Here for Wil’s Free Stronger Than Ever Weightlifting Program

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Becca Borawski Jenkins.

Janda graphic courtesy of The Janda Approach.