Depending on how old you are you may recall a time when scores were kept at junior sporting events and medals were handed out for first, second, and third places. You may also remember a time where you were given an “F” for failing and, depending on how good you were, an “A” for passing.

But you also may not even know a time like this existed. During the late 1990s there was hope and anticipation for the new millennium and what would it hold for our kids. Would they go down the same path as the Y2K bug or would they continue to carry the evolutionary dreams of humanity? Experts collaborated and decided to rewrite the textbooks (although looking back now, I bet they wish they could rewrite the history books). It is quite obvious that the resulting experiment went horribly wrong and what now seems to be an accepted practice has proven to be a miserable failure.

I am talking about the “effort for participation” theory, which states that kids should not be made to feel like they came first or last, won or lost, or passed or failed. This theory said kids should be made to feel that participation is more important than competition, and what matters most is the effort they put in. While this statement does have truth and I wholeheartedly agree with reward for effort, did anyone stop to think about the kids who actually tried hard and were encouraged to do their best? The kids who gave their all because they were motivated by the idea of receiving a first place ribbon for their work?

According to the National Institute of Health, 40% of kids who grew up in this era believe they should be promoted every two years regardless of performance. Apparently they received so many participation trophies that they justify and warrant this type of thinking. Now, can we call these people lazy? Well here’s a statistic that may just answer that. In 1992, the non-profit Families and Work Institute reported that 80% of people under 23 wanted to one day have a job with greater responsibility. Ten years later only 60% felt this way. And we can guess how it might trend from there.

So why did the “experts” take this approach? Well according to psychologists, counselors, and many textbook warriors, it was believed that the stresses of winning and losing were way too much for kids to handle and they should not be judged or scored on their performance, but rewarded for their efforts. While this may be all warm and fuzzy, it has created a generation who believe that no matter what happens they are entitled to the accolades of winning because they made the effort to participate. Can this type of attitude be beneficial for the advancement of technology and individual sporting accomplishments? Let’s take a closer look at some sporting greats past and present.

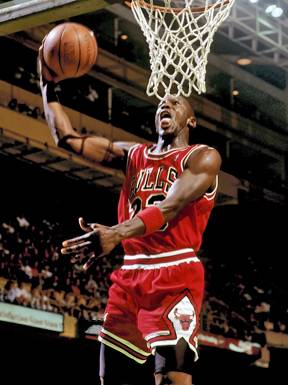

One athlete that comes to mind is none other than Chicago Bulls legend Michael Jordan. Would he have become so great if he weren’t dropped from his high school basketball team? Would the world have ever witnessed perhaps the greatest basketball player to ever live if he was kept on the team because he was entitled to it? Michael Jordan defied all the odds, and while I don’t think every kid can be like him, I am sure there were millions of children around the world who were inspired by his journey to greatness and used this as motivation to work harder for their goals.

One athlete that comes to mind is none other than Chicago Bulls legend Michael Jordan. Would he have become so great if he weren’t dropped from his high school basketball team? Would the world have ever witnessed perhaps the greatest basketball player to ever live if he was kept on the team because he was entitled to it? Michael Jordan defied all the odds, and while I don’t think every kid can be like him, I am sure there were millions of children around the world who were inspired by his journey to greatness and used this as motivation to work harder for their goals.

In this regard, you also can’t overlook the feats of soccer giants Manchester United. For over twenty years they have dominated world soccer and produced some of the greatest players ever seen. When Alex Ferguson was asked what makes his team so successful he replied, “We can’t handle coming second.” A statement so true and simple that it epitomizes the driving force behind every athlete’s motivation to win. They simply can’t handle coming in second. Participation is not enough. What makes these athletes and sporting teams so great is that they push the physical and mental boundaries of training to be better than their competition. These are the same boundaries pushed academically by doctors and scientists to find cures and medicines for some of the world’s most crippling diseases. I would hate to think what would have happened if these geniuses had been rewarded simply for effort and were not pushed to their absolute limits of human potential.

Kids should “participate” in sports, but they should also be encouraged to try to win. “Try” being the operative word. Trying to win may be more important than the act of winning. But when we take away a child’s desire to try for something than what does he or she have to strive towards? Perhaps I can sum it up best in the words of great NFL coach Vince Lombardi:

The spirit, the will to win, and the will to excel – these are the things that endure and these are the qualities that are so much more important than any of the events that occasion them.”

There’s only one way to succeed in anything, and that is to give it everything. The difference between a successful person and others is not a lack of strength, not a lack of knowledge, but rather in a lack of will. The score on the board doesn’t mean a thing. That’s for the fans.

If you’ll not settle for anything less than your best, you will be amazed at what you can accomplish in your lives.

Last year Time magazine wrote an interesting article, The Me Me Me Generation, outlining what society had hoped to achieve with this 1990s experiment. Only now are we starting to see the results of the “effort for participation” theory, which in my books would be handed a big fat “F” for fail but unfortunately we can’t do that anymore, so we must settle for a simple “E” for effort and “P” for participation.

Let your kids participate and compete. The score will take care of itself.

References:

1. National Institutes of Health, ”NIAMS Kids Pages.” Accessed 04/02/14

2. Families & Work Institute “Families & Work Institute Research & Publications.” Accessed 04/02/14

3. Stein,J., “The Me Me Me Generation,” Time Magazine. Accessed 04/02/14

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 by Steve Lipofsky at basketballphoto.com [GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons.