Now that everyone is utilizing single-leg training, surely they have figured it out. But I suggest not. As I outlined in part two Challenging The Overreaction, there are many ways that the majority are undermining the power of single-leg training. In the following I share seven key strategies that will help you make the most of it.

All parts of these series:

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 1: Historical Perspectives

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 2: Challenging The Overreaction

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 3: 7 Key Practical Strategies – You are here

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 4: Correcting The Imbalances

#1 Progress Along a Continuum From Unilateral to Bilateral

When I released my single-leg training concepts to the broader market in the late 1990s, there was never any suggestion they should replace bilateral exercises. In fact if you studied the original Get Buffed! and Limping programs, you will note I progressed from a dominance of single leg or unilateral leg exercises to a dominance of bilateral leg exercises.

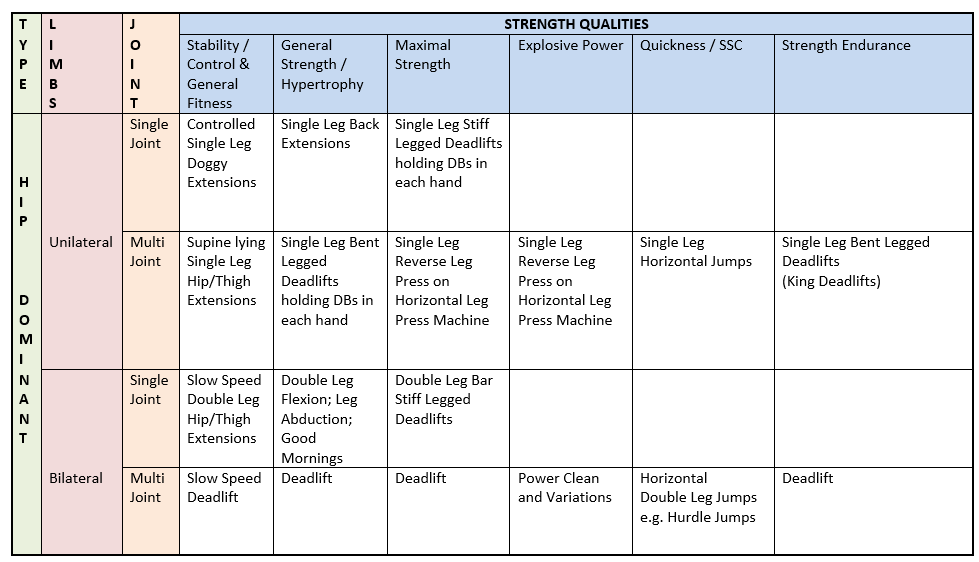

My next and final step is to divide all the above into unilateral and bilateral, and single and double/multi-joint exercises (refer Figure 5 and Tables 7-16). Note these tables give examples of exercises that suit both the family tree, the number of limbs and joints involved, and the training method/desired adaptation.3

What I am seeing again is that overreaction I spoke of with unilateral leg exercises being touted as superior to bilateral. I suggest it is not accurate or beneficial to take this simplistic viewpoint. All training decisions should be ideally fully individualized.

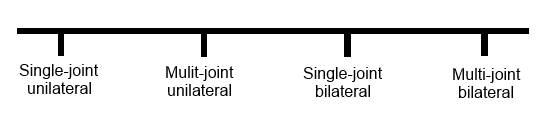

I created extensive guidelines showing exercise progressions from unilateral to bilateral within each line of movement. These tables were original works. In the simplest form regarding joint involvement, the tables available in the How to Write book work on a continuum as per below:4

Lower body exercise options as per the hip-dominant, lower-body family tree:5

#2 Always Retain the Lower End of the Continuum

As an extension of the above point, where possible always stay in touch with the exercises that are being deemphasized in any given phase. The challenges with neglecting any exercise for a long period of time include a detraining of its specific benefits and increased DOMS when one returns to the exercise.

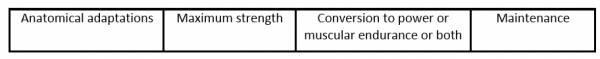

For example, even in Stage 1 of the Get Buffed! and Limping programs, where single-leg, lower-body exercises dominate, you can still see a trace of bilateral exercises. And vice versa, as the program unfolded towards the fourth and final stage with dominance in bilateral loaded movements, you will see some exposure in a maintenance level towards the lower load unilateral exercises.

Typically I would place the maintenance movements towards the end of the program. The below table is a simplistic representation of this:

#3 Prioritize Hip Dominant Over Quad Dominant

Prior to my release of the lines of movement concept, the lower body was typically treated as one. Following my introduction of distinction between quad- and hip-dominant exercises, and the subsequent take up of this idea universally, I would have expected a much greater working application of this concept. I have been seriously disappointed with the failings of this powerful concept to make enough of a difference. I believe in part this is due to those who took it upon themselves to teach my concept, but were themselves not in mastery of it in the practical application sense.

I understand I am going to have to champion the concern about quad dominance in strength training trends globally for much longer than I originally expected. One of the greatest challenges faced in attempting to teach the world how to ensure balance in their program is that for the most part the average trainer makes decisions based on social bias, i.e. what most others are doing. I believe that training trends are currently driven more by marketing forces than by rational, objective, and intuitive thinking.

It appears there is significant peer pressure to use a certain training tool or cutting edge training exercise or method. As the decisions are made more and more by marketing trends and humans need to conform, I am seeing a movement away from objective thinking.

So I am going to say this simply. Get ready to lead with hip-dominant exercises. When I say lead, I mean to place them first in the workout and the week, and do them in higher volume:

- If you are currently balanced between hip and thigh musculature and strength, then lead with hip-dominant exercises most of the time.

- If you recognize you are imbalanced in this department, typically from years of imbalanced training (until you read my writings) – then expect to lead with hip-dominant exercises for a number of years to come.

- If you are really in trouble, i.e. your quad dominance over hip dominance is causing or will cause you serious grief, then be willing to drop all quad-dominant exercises indefinitely until you have ascertained you are balanced again.

#4 Manipulate the Ratio of Left to Right Reps

Another strategy to rebalance your quad and hip dominance is to manipulate the ratio of strong side to weak site reps. Here is what I wrote on the matter:6,7

Instead, plan to use unilateral movements (i.e. one limb at a time), applying my ‘Weak Side’ rules:

- Do the weak or injured side first.

- Then maybe do the strong side.

- Do no more reps or load (strength) or time (stretching) on the strong/long sides than the weak/tighter side could do;

- If the imbalance is greater than 10%, or thereabouts, consider doing a lower ratio of reps on the strong side to the weak side. If the weak side can only do 10 reps, do only 5 reps on the strong side (or two sets on the weak side to one set on the strong side); or do 10 minutes of stretching on the tight side but only 5 minutes on the long side. This is a ratio of 2:1, weak side to the strong side. If the imbalance is greater than-50 %, consider doing no work on the strong side at all.

Here’s a way you can work this even in a class situation. Let say you were doing a semi-unilateral, alternated-leg drill such as lunges. You recognize the need to show bias in reps to the weak side, but you don’t want to get out of sync with the class. You work a ratio on a needs basis, e.g. three reps on the weak side, one rep on the strong side. You keep going with this until you achieve your desired number of reps or time expires.

#5 Respect the Need to Counter Downsides of Strength Training

I have noted a bias in U.S.-influenced training methodology towards strength. Now, in theory, this might seem great, especially to those who believe higher strength levels mean better athletic performance. I don’t. My belief is that all things being equal, it may serve you. But as individual’s strength increases, it’s rare that all things stay equal. What typically happens as people get stronger is that they change in their muscle length and tension for the worse.

To help you understand this concept, I share from my writings from early in the 2000s:

T: Next category: Injury prevention.

Ian: This is the way the game is played. Most people go the gym and create problems. They don’t know it, but they’re creating problems. Most programs – including those being promoted as “guru” programs – are creating problems. It’s a simply trade-off between instant gratification and delayed long-term results. Sure, you might get a pump today, but in three years’ time you’re having surgery, or you can’t train for 12 months. How does it feel to put in those 5000 hours and find out you’ve only created an injury?

T: Is this caused mostly from a lack of stretching?

Ian: Stretching is involved; it’s one of the components. But it’s also the balance between the muscles. When you f*** with the body’s length, tension and stability, you’re going to create a problem. The joints were designed to move relative to each other in a certain way, and when you apply a powerful stimulus such as weight training, you could, for example, change the way the shoulder rotates in the joint because of your program. You’re just f****** that joint. There is no other way to describe it.8

Soft tissue length, tension and joint stability – the keys to joint health and injury prevention.

Whilst simplistic in concept, a mastery of the optimal condition in soft tissue length, tension and joint stability, for each individual athlete in each joint in relation to specific activities would result in significant reduction in injury incidence and severity. This simple concept is worth the effort to master.9

For anyone wanting to learn more about how to manage, prevent, or rehab injuries to the joints of the lower body in particular the knees, you will value this:

Safeguarding the knee becomes a game of controlling the length and tension of the soft tissue.

For the pain to commence with impaired function of the muscles that support the knee, you’re looking for either reduced length of the connective tissue or heightened tension in connective tissue.

So if the pain is under the kneecap or in the joint, stretching/adjusting the tension in these tissues may help. So if the pain is lateral, medial or under the kneecap, stretching/adjusting the tension in these tissues may help. So if the pain is medial or under the knee cap, stretching/adjusting the tension in these tissues may help.10

#6 Technique Does Matter

There is significant pressure and influence from a variety of circles to “go heavy or go home.” That’s fine, but I suggest that technique is still more important than loading. And just because you are engaging in the all-conquering, single-leg training does not exempt you from this.

I prioritize technique because of my focus on selective recruitment:

…Load is over-rated – if you do not have technique, if you do not have selective recruitment, you are increasing the risk to the athlete by exposing them to that loading. So if it is one thing I teach you it is get that recruitment, get the technique, prioritize that over the loading. The athlete is not getting judged in athletic success by how much they lift in the gym so why take risks in the gym…11

And my belief that load-induced technique breakdown is highly correlated with injury:

Not only does the excessive focus on loading have questionable superior transfer, it also involves greater injury risks for a number of reasons. Firstly, higher loading may result in a higher incidence of trauma e.g. torn muscles, ligaments. Secondly, the added loading increases joint wear, which over time will accumulate and manifest as an ‘injury’. Thirdly, the athlete will inevitably compromise technique to lift heavier, and develop muscle imbalances as a result.12

This does not mean I question the value of loading:

Loading (intensity) is an important variable, in most cases more important than volume. However loading in strength training is an attraction that blinds the user to the downsides or limitations of loading. There are a number of situations where loading is used inappropriately, and with a high cost.13

I simply believe you will get a better transfer to the function you are training for, and fewer injuries along with it, if you prioritize loading.

#7 Prepare the Joint Before Loading It

There is no doubt that I have a long and large respect for single-leg training, having pioneered, championed, and innovated in this area for the last few decades. What I want to stress, though, is that just because single-leg training is great, doesn’t mean it comes without downsides.

Those that can recall my Opposite and Equal principle know what I am talking about here:

This is a very interesting principle, a concept that I have created. …The concept is based on the belief that to every action (in training) there is a positive and a negative outcome, and that often the negative outcome is equal or as powerful as the positive outcome.14,15

One of the major concerns or downsides presented by single-leg training is that in essence you double your load immediately – and that’s just if you are using bodyweight as opposed to additional external loading. This places an additional burden on you, assuming you wish to have longevity in your joints, to adequately prepare the joint for loading.

There are a number of progressions I recommend:

- You have to stretch before loading, especially the muscles of the knee and hip.

- Dynamic stretching is not adequate (in fact, I don’t believe it should be called stretching). You need stretching methods more conducive to creating length, such as static. Yes, I know what you are thinking because I have been dodging the stone throwing for my heresy for many years now.

- The older you are and the more damaged your joints are, the more you need to do this – and the more you should have done it before you got to this point.

- My concept of control drills (another original innovation) will also serve to protect the joint.

- You can and should consider open-chain (off your feet – yes, I know more stones) exercises in the progression to closed-chain (on your feet).

- Do bilateral before unilateral exercises.

- Use bodyweight before external loading in the micro and macro sense.

Conclusion

I have more strategies that I could teach, but as was the case when I first introduced single-leg training into the mainstream consciousness (e.g. the Limping program), I will intentionally hold back because I know I have pushed the boundaries of acceptance in challenging your thinking. After all, I have suggested some “radical” ideas.

The irony is that single-leg exercises were once challenging and heretical. Now they are mainstream. I am totally confident that what I have shared above will follow that same path, so why wait until everyone is doing it? Benefit from this information now.

In part four Correcting The Imbalances I will focus on the challenges and solutions ahead in the application of single-leg training.

All parts of these series:

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 1: Historical Perspectives

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 2: Challenging The Overreaction

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 3: 7 Key Practical Strategies – You are here

- Unilateral Leg Training, Part 4: Correcting The Imbalances

References:

1. King, I., 1999, Get Buffed (book

2. King, I, 1999, “Twelve Weeks of Pain, Part I – Limping into October“, T-nation.com, Fri, Sep 17

3. King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 40

4. King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 42-49

5. King, I., 1998, How to write strength training programs, p. 49

6. King, I., 1999, Question of Power, t-mag.com, No. 43, March 12 1999

7. King, I., 1999, Question of Power, Q & A column with Ian King, t-mag.com. No. 43, 12 Mar 1999

8. King, I., 2000, in Shugart, C., Meet The Press – Coach of coaches: An interview with Ian King, 29 Dec 2000, t-mag.com

9. King, I., 2005, The Way of the Physical Preparation Coach, p. 67

10. King, I., 2003, King, I., 2003, Out of Kilter III – End needless knee pain! t-mag.com, 28 Nov 2003

11. King, I., 2000, How to Teach (DVD)

12. King, I., 1997, Winning and Losing, p. 44-45

13. King, I., 2005, The Way of the Physical Preparation Coach, p. 47

14. King, I., 1997, Winning and Losing, p. 38-39

15. King, I., 1999/2000, Foundations of Physical Preparation (course/book) p. 30-31

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.