Give two athletes of the same sport the same task. One athlete may be able to repeat this task again and again without issue. The other may be unable to complete this task even once.

The concept of periodization for athletics is not a new concept, but its usage is of fundamental importance to anyone looking to make systematic improvements in their training and involve the often-forgotten variable of individualization.

Give two athletes of the same sport the same task. One athlete may be able to repeat this task again and again without issue. The other may be unable to complete this task even once.

The concept of periodization for athletics is not a new concept, but its usage is of fundamental importance to anyone looking to make systematic improvements in their training and involve the often-forgotten variable of individualization.

READ MORE: Understanding Periodization: A Guide for Coaches and Programmers

What Does Periodization Mean?

Periodization is defined as the “long-term cyclic structuring of training and practice to maximize performance to coincide with important competitions.”1

Simply, it is the program design strategy that governs planned, systematic variations in training specificity, intensity, and volume.

The goal with periodization is to maximize your gains while also reducing your risk of injury and the staleness of the protocol over the long term.

It also addresses peak performance for competition or meets. Periodization, if appropriately arranged, can peak the athlete multiple times over a competitive season (Olympic weightlifting, powerlifting, track and field) or optimize an athlete’s performance over an entire competitive season like with soccer or basketball.

Think of periodization as a continuum. When we desire a specific training objective, such as an increase in vertical jumping ability or an increase in 1RM squat strength, it does not matter what phase the training is in.

Rather, we should focus our energy on the training stimulation being applied during this objective, and ensure it features extensive repetitions and volume without the chance of different stimulation that would disrupt the adaptation changes taking place.

“The goal with periodization is to maximize your gains while also reducing your risk of injury and the staleness of the protocol over the long term.”

An intelligently designed training year will encompass smaller blocks of time that each has its own goals or priorities.

This type of overall schedule will encompass all of the aspects of the athlete’s programming and can include strength training, conditioning, plyometrics, and sport-specific activities.

Why Do You Need Periodization?

There are numerous proven benefits to utilizing a form of periodization for your planned progression:

- Management of fatigue, reducing risk of over-training by managing factors such as load, intensity, and recovery

- The cyclic structure maximizes both general preparation and specific preparation for sport.

- Ability to optimize performance over a specific period of time

- Accounting for the individual, including time constraints, training age and status, and environmental factors.

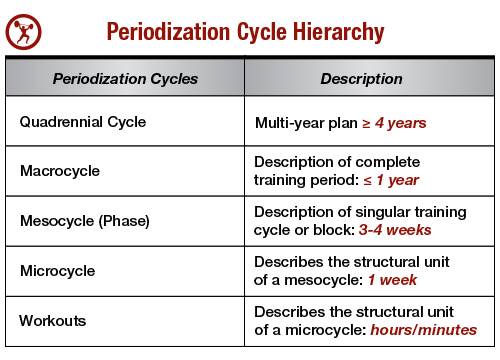

As we move forward it will be helpful to understand the basic structuring of a periodization cycle. See the graph below for a simple breakdown:

Semantics causes problems in understanding periodization. You could have two individuals yelling at each other in a conversation about periodization where one is comparing “block periodization” to some form of “linear periodization” or someone else is comparing “conjugate method” with “concurrent periodization.”

The problem with both of these examples is that linear and block are the same foundational concept, as is the case with conjugate and concurrent.

The underlining goal for any serious competitor is understanding that you cannot say periodization is one way. It has many different profiles and progressions.

RELATED: Block Periodization Versus Linear Periodization: Which Is Better?

Traditional Model: Linear Periodization

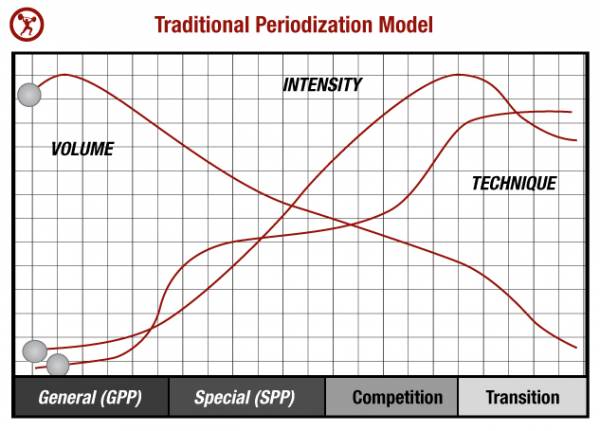

The traditional model in the classical sense is simply making changes in both volume and intensity across multiple mesocycles. This model is most appropriate for beginner strength athletes or an athlete’s general preparation for sport.

This model provides a concurrent development of strength, respiratory, and technical abilities.

This model is characterized by longer training periods, less reliance on super compensation, and a focus of more general training over specific. The model lays out planned progression in the following way:

The phases involved are a General Preparatory Phase (GPP), Special Preparatory Phase (SPP), Competition Phase (C), and Transition Phase (T).

The benefits to using this form of periodization are an overall development of multiple qualities that are important to performance, as well as a way of being able to focus more on the general overall training effect of strength development.

That being said, traditional modeling has proven unable to provide a multi-peaking approach to in-season performance or sufficient training stimuli to help intermediate-to-high level athlete’s progress.

This is mainly due to its “mixed” or simultaneous development of motor abilities and skills.

RELATED: Linear vs. Nonlinear Periodization: Which Is Better?

Non-Traditional Model: Undulation

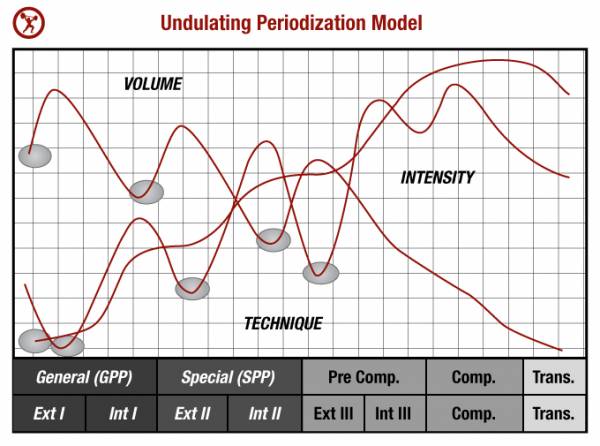

The non-traditional model of periodization, referred to as undulating, has gained traction in recent years.

The undulating design is based on the concept of Hans Seyle’s General Adaptation Syndrome. G.A.S. explains the way your body restores itself to balance, or homeostasis, when faced with stressors.

With undulating design, there is enough variation in stressors to continually make progress without allowing your body to fully adapt to all the stressors taking place. All this while still accounting for the recovery or restoration needed.

In undulating design, the stimulus is varied either within a weekly model (WUP) or in daily undulating periodization (DUP) where daily changes are made to either volume or intensity.

Studies like the Rhea study in 2002 have shown this modeling can be more favorable for increases in strength gains than in typical linear modeling in well-trained athletes.2

This study also purported that DUP may be more beneficial for elite athletes as it helps them avoid the dreaded plateau effect that can happen in well-trained lifters.

DUP modeling has also showed a favorable increase in strength gains and CNS adaptation without the added muscle mass, which could benefit athletes in groups where weight classes are of importance.

More research needs to be done in this area. One of my mentors, Dr. Zourdos, is helping to lead this charge with multiple studies currently in review.5

“With undulating design, there is enough variation in stressors to continually make progress without allowing your body to fully adapt to all the stressors taking place.”

Advanced Model: Conjugate Sequence/Block Periodization

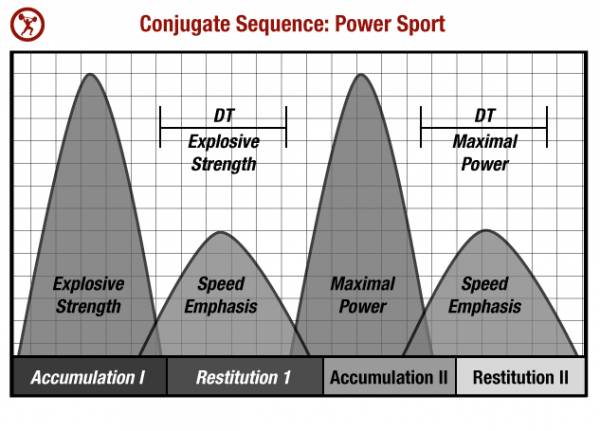

Lastly, we need to begin an understanding of the conjugate sequence model, or the model more commonly known as block periodization. This advanced concept model was introduced by noted strength professor Yuri Verkoshansky.

Many individuals confuse this approach with the Westside Barbell system, or conjugate method, developed by Louie Simmons.

Verkoshansky has stated on numerous occasions that Louie took different concepts from different systems, and simply used the term conjugate to mean a marrying of training concepts, or a running of these concepts concurrently.

He did not use the original conjugate sequence system itself as designed by Verkoshanky. There is a reason why, but that is better suited for another article.

Block periodization, or the conjugate sequence, was originally developed by Verkoshansky for Olympic athletes, i.e. the most elite-athletes on the planet.

It consists of a two-block design, accumulation and restitution. In the accumulation blocks, the focus is directed toward supporting motor abilities while simultaneously developing certain strength qualities necessary for the athlete with a limited volume load.

The restitution block is essentially the opposite. They support strength qualities in the athlete, while addressing the development of specific, technical motor qualities with a limited volume load. These training loads must target different abilities (max-strength, explosive strength, max anaerobic power, etc.).

“Block periodization, or the conjugate sequence, was originally developed by Verkoshansky for Olympic athletes, i.e. the most elite-athletes on the planet.”

Basically, in the accumulation block we are looking for unilateral concentrated loading of strength qualities. This unilateral increase in concentration of loading will allow specific systems to achieve a higher level of stress.

This, as we know already, is needed for further adaptation to take place in elite level athletes. While you are focused on this, you are also training to keep the motor abilities necessary for your sport.

In the restitution blocks, we are flipping it around. We are looking to support the strength qualities developed in the athlete while improving the technical motor qualities that are needed for the athlete’s sport.

Putting It All Together

Start simply. If you have been training consistently for less than two years, you are a beginner in training age.

Start with the traditional model and assess the progress and variations within that model. In other words, exhaust your ability to continually make progressive changes to your strength without seeing a decrease in performance or plateau effect.

A basic example of a linear periodization setup is the popular five sets of five repetitions on core exercises such as squat, bench, deadlift, and power clean.

Add five pounds for upper body movements or ten pounds for lower body movements every training session in a progressive fashion until plateau. Reset and begin again.

If you are an intermediate trainee, then look at some form of the undulating periodization model and its progressions. You could undulate your training intensities or volume on a weekly or daily basis.

For instance, utilizing the squat exercise for hypertrophy within the first phase of your undulating block, you could do something like this for volume:

- Week 1: Squat, 3 Sets X 12 Reps

- Week 2: Squat, 4 Sets X 8 Reps

- Week 3: Squat, 5 Sets X 6 Reps

- Week 4: Squat, 3 Sets X 5 Reps

From there, you could move into a strength block using 6/4/2 for example. Then, if you had a competition on the horizon, you can move into a power block.

If no competition is near, you could go into another hypertrophy block. Rinse and repeat. Just make sure you are adjusting volume as intensity goes up. These two things have an inverse relationship.

RELATED: 3 Keys to Successfully Peaking for an Event

This article is not really geared towards the advanced-level athlete so there is no need at this point to lay something out using the conjugate sequence system.

Most trainees fall into the first two categories I have mentioned, and there is more than enough to concern yourself with in those categories.

Putting Periodization Into Practice

Periodization has stood the test of time for the simple fact that there are so many progressions and ways to structure your training so that you can be at your best when it matters most.

Failing to utilize any form of periodization for your training could lead to overtraining, failure to recover appropriately for progression, and the inability to see the progress you deserve from the time you put into training.

If you are interested in learning more about periodization theory and concepts you can check out the works by Tudor Bompa, Vladimir Issurin, Yuri Verkhoshansky, Gregory Haff, and A.S. Medvedyev.

References:

1. Verkhoshansky, Y., “Sport Strength Training Methodology”. Comment on Magnush. 2007

2. Rhea, MR, et al., “A Comparison of Linear and Daily Undulating Periodized Programs With Equated Volume And Intensity For Strength,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2002, 16(2), 250–255.

3. Painter, K. “ Practical Comparison between Traditional Periodization and Daily-Undulated Weight Training Among Collegiate Track and Field Athletes,” East Tennessee State University, 2009.

4. NSCA. “Athlete Profiling: Choosing A Periodization System To Maximize Individual Performance”. Conference Lectures. 2012

5. Zourdos, MC. “Optimizing Periodization and Program Design Muscle Performance Adapations,” ISSN Optimal Human Performance, 2014.

6. Baechle, Thomas R., Earle, Roger W. (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Nebraska. Human Kinetics.

7. Issurin, V., “Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review,” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 2008, 48(1):65-75.

Photos courtesy of CrossFit Impulse.